One of my earliest and most frightening memories is the time I became separated from my mother in one of last century’s massive department stores. I must have let go of her hand, or she mine; which one of us wandered off I will never know. I looked around, and suddenly, inexplicably, she was nowhere in sight. I felt pure terror. In the busy aisles, unfamiliar adults brushed passed me with cold impassive faces.

One of my earliest and most frightening memories is the time I became separated from my mother in one of last century’s massive department stores. I must have let go of her hand, or she mine; which one of us wandered off I will never know. I looked around, and suddenly, inexplicably, she was nowhere in sight. I felt pure terror. In the busy aisles, unfamiliar adults brushed passed me with cold impassive faces.

Abandonment is one of our primal fears. For nine months, we inhabit our mother’s body, completely dependent on her for life-giving essentials. When the umbilical cord is cut, we become separate beings, unmoored from our source. Unlike other primates, at birth we are helpless and dependent.[1] Humans develop self-sufficiency at a slower pace than our primate cousins and remain immature longer than most. Without an attentive caregiver, our early existence is precarious.

Before Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, speculated that separation from our mothers at birth is the central trauma of our lives[2], European philosophers, among them Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre, theorized that fear of abandonment is a major component of modern consciousness. What they understood — the existential nature of our anguish, despair, and aloneness — we now embrace as a condition of our post-modern psyches.

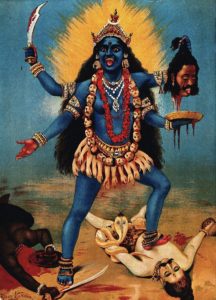

Long before these renowned thinkers espoused their theories, our foremothers sat around a fire exchanging wisdom tales. P.L. Travers, author of the Mary Poppins series, shares her literary detective work: “When a woman is the chief character in a story, it is a sign of its antiquity. It takes us back to those cloudy eras when the world was ruled not, as it was in later years, by a god but by the Great Goddess.”[3]

Maternal mortality, dying while giving birth or thereafter, must have been high on women’s lists of ever-present dangers to their lives. Medical historians Van Leberghe and Debrouwere estimate that maternal mortality could have been as high as 25% in prehistoric times.[4] In traditional societies, a solicitous maternal presence insured safety, security, survival. Her absence could be catastrophic, often presaging an arduous struggle for her offspring for food, shelter, and love.

Common wisdom often comes down to us through folk and fairy tales. So it is not surprising that the tragic event of a mother’s death or absence, due to separation or illness, found its way into them. These cautionary tales illustrated the challenges an orphaned child might encounter after such a grievous loss: loneliness, poverty, despondency, victimization by revenge, competition, jealousy, envy, greed. The tales don’t just depict these woes, some were maps to transformation, from naïve and untested young girls to brave, self-sufficient young women. For heroes, the transformation required a warrior stance, slaying the enemy or killing the monster. But for heroines, the prescription was the deployment of charm, wit, cunning, generosity, kindness, gratitude, and respect for nature. Remedial attributes and virtues, rather than sheer courage and brawn, secured her success over malevolent forces.

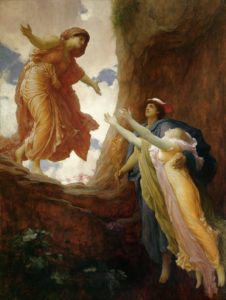

Many well-known tales begin with a mother’s death. Most often, though not exclusively, stories about mothers and daughters start in this manner. (“Cinderella” and “Snow White” are the best-known examples in the United States.)

Many well-known tales begin with a mother’s death. Most often, though not exclusively, stories about mothers and daughters start in this manner. (“Cinderella” and “Snow White” are the best-known examples in the United States.)

In fairy tales, as in dreams, the opening event presents the initial situation or predicament that sets the story’s action rolling. “Vasilisa The Beautiful,” a Russian tale, begins with these words:

In a certain Tsardom, across three times nine kingdoms, beyond high mountain chains, there once lived a merchant. He had been married for twelve years, but in that time there had been born to him only one child, a daughter, who from her cradle was called Vasilisa the Beautiful. When the little girl was eight years old the mother fell ill, and before many days it was plain to be seen that she must die. So she called her little daughter to her, and taking a tiny wooden doll from under the blanket of the bed, put it into her hands and said:

“My little Vasilisa, my dear daughter, listen to what I say, remember well my last words and fail not to carry out my wishes. I am dying, and with my blessing, I leave to thee this little doll. It is very precious for there is no other like it in the whole world. Carry it always about with thee in thy pocket and never show it to anyone. When evil threatens thee or sorrow befalls thee, go into a corner, take it from thy pocket and give it something to eat and drink. It will eat and drink a little, and then thou mayest tell it thy trouble and ask its advice, and it will tell thee how to act in thy time of need.” So saying, she kissed her little daughter on the forehead, blessed her, and shortly after died.

The death of the mother precipitates the daughter’s journey to find her way in a seemingly cruel world. Bereft of a tender, caring maternal presence, sorrow and woe besiege the grieving child, a trope much more common in stories about a daughter’s loss of her mother than a son’s. In both cases, the abandoned child must “grow up,” that is, become her own true self; but the masculine-identified child is encouraged to take immediate action, while the feminine-Identified child is encouraged to suffer through the hardships. However, the tales also indicate that without the initial difficulty, abandonment, the heroine would not be required to discover her courage, self-respect, self-worth, and maturity.

In some tales, the mother figure is not dead but metaphorically “missing.” She is emotionally neglectful, passive, or narcissistic and inadequately loving, like the mothers of “Rapunzel” and “Hansel and Gretel.” Or she is beholden to her male counterpart. The consequences of having this type of mother are just as devastating as if she had died.

What do we make of all the wicked stepmothers? The frequency with which they appear indicates a truth about human wholeness. No person is all-good, all-giving, all-knowing. No human is without anger, jealousy, greed, what Carl Jung called the repressed shadow, the split-off and unacceptable aspect of our psyches. In the tales, the negative qualities society rejects are projected onto the figures of the wicked stepmother, the witch, and the hag.

Woe to him who thinks to find a governess for his children by giving them a stepmother! He only brings into his house the cause of their ruin. There never yet was a stepmother who looked kindly on the children of another; or if by chance such a one were ever found, she would be regarded as a miracle, and be called a white crone.

So begins the Italian tale of “Nennillo and Nennella.”

What mother hasn’t had moments of anger, frustration, exhaustion, and resentment and felt like a monster? What mother hasn’t wanted, against her best judgment, to lash out at a child? How shameful we feel accepting our emotionally-nuanced humanity!

In fairy tales, the dead or missing birth mother is idealized and angelic. In “Cinderella,” the perfect mother is represented by a fairy godmother who appears when Cinderella’s need is urgent. Like all good fairy godmothers, she supplies the necessary goodies for Cinderella’s transformation. In “Vasilisa the Beautiful,” before Vasilisa’s mother dies, she gives her daughter a wooden doll, a stand-in for a fairy godmother, and a perfectly attuned maternal presence.

Both fairy godmother and magical doll represent the capacity of an abandoned child to internalize and elicit “the good mother” within. Despite early life disturbances, through facing adversity, the child develops the ability to trust her inner resources and intuition. Stories like “The Handless Maiden,” “Vasilisa The Beautiful,” and “The Miller’s Daughter” in which the heroine must perform a series of impossible tasks show the development of self to a greater degree. Help also comes from the natural world, from a frog that appears on the path, a wise bird, a friendly wind, and here, too, the heroine must consult her inner wisdom in deciding where to put her trust.

Both fairy godmother and magical doll represent the capacity of an abandoned child to internalize and elicit “the good mother” within. Despite early life disturbances, through facing adversity, the child develops the ability to trust her inner resources and intuition. Stories like “The Handless Maiden,” “Vasilisa The Beautiful,” and “The Miller’s Daughter” in which the heroine must perform a series of impossible tasks show the development of self to a greater degree. Help also comes from the natural world, from a frog that appears on the path, a wise bird, a friendly wind, and here, too, the heroine must consult her inner wisdom in deciding where to put her trust.

Human wholeness admits we are complex creatures: generous AND selfish, caring AND disengaged. In fairy tales, as in dream work, we can interpret all the characters, including the non-human ones, as “parts” of our psyches. We are the needy helpless children, AND we are brave heroines/heroes. We are Beauty AND we are the beast. We can be sturdy as a tree, blown about like a feather. We burrow in the mud of not-knowing, like frogs. We open our petals in the sunshine, like fragrant roses. Every aspect of a tale can be interpreted and considered symbolically for a more expansive and revelatory understanding of our nature.

The fantasy ending “of happily ever after” can be re-visioned with the knowledge that our suffering does not preclude joy and transformation, possibility and fulfillment. What the tales tell us is that we may be alone, but we are not forsaken; we are part of a vast universe in which helpful forces abound.

[1] Wong, Kate, “Why Humans Give Birth to Helpless Babies,” Scientific American, August 28, 2012

[2] Freud, Sigmund, The Interpretation of Dreams, “The act of birth is the first experience attended by anxiety, and is, thus, the source and model of the affect of anxiety.”

[3] Travers, P. L., About Sleeping Beauty (1975), p. 59

[4] Van lerberghe, Wim and Vincent Debrouwere, “Of Blind Alleys and Things That Have Worked: History’s Lessons on Reducing Maternal Mortality,” Research Gate, November 2000

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

If you found this blog interesting, you may also enjoy “How Snow White and Her Cruel Stepmother Help Us Cope with Evil,” “Mothers, Witches, and the Power of Archetypes,” and “Write Your Own Fairy Tale.”