Enchantment. I hope the word sends a thrill up your spine! When was the last time your conversation turned to enchantment? Who talks about enchantment these days? That may be one of the reasons it interests me. As a writer, I’m interested in what isn’t being said in the public sphere—the unsaid and the unspoken.

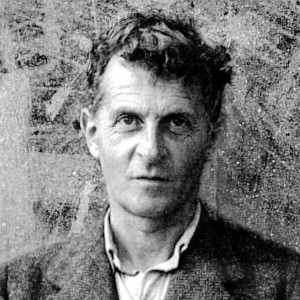

The German philosopher Wittgenstein explored the subject of enchantment.  According to him, enchantment transports us beyond our finite selves. To be enchanted, he wrote, was “to show the fly the way out of the bottle.” To show the fly the way out of the bottle! The French poet Paul Eluard said, “There is another world, but it is in this one.” I agree. Enchantment is with us here, now.

According to him, enchantment transports us beyond our finite selves. To be enchanted, he wrote, was “to show the fly the way out of the bottle.” To show the fly the way out of the bottle! The French poet Paul Eluard said, “There is another world, but it is in this one.” I agree. Enchantment is with us here, now.

And yet we seem so attracted to enchantment’s opposites—cynicism, irony, mistrust—qualities that show up in lots of contemporary fictional characters who reflect our twenty-first century discouraged and disenchanted point of view. Enchantment, instead, would have us stand in the place of wonder and consider ourselves apprentices in the mystery of Being.

I’ll share a recent discovery—the role enchantment has played in my writing— and how the enchanted state in a writer, in this case me, seeps into the work itself. Another way of saying this is that what’s in the psyche of the writer shows up transmuted on the page. Transmuted is key because sometimes only the slightest aroma of the original idea is evident in the final written form. Think of it this way: The rapture expressed in Mozart’s The Magic Flute is directly related to the rapture Mozart presumably felt while composing it. If Mozart was filled with rapture, rapture will be in his music.

and how the enchanted state in a writer, in this case me, seeps into the work itself. Another way of saying this is that what’s in the psyche of the writer shows up transmuted on the page. Transmuted is key because sometimes only the slightest aroma of the original idea is evident in the final written form. Think of it this way: The rapture expressed in Mozart’s The Magic Flute is directly related to the rapture Mozart presumably felt while composing it. If Mozart was filled with rapture, rapture will be in his music.

There’s plenty of enchantment going on in my novel The Conditions of Love. (Check out Mr. Tabachnik’s relationship to opera, or Eunice and Rose’s relationship to the natural world, or Mern’s intoxication with Hollywood.) I myself was in an enchanted state while writing a lot of the book, but I also admit that my characters, in turn, enchanted me. This is the moment when I might explain that the novel’s origins began when I started to hear voices, but that’s another story for another time.

There’s plenty of enchantment going on in my novel The Conditions of Love. (Check out Mr. Tabachnik’s relationship to opera, or Eunice and Rose’s relationship to the natural world, or Mern’s intoxication with Hollywood.) I myself was in an enchanted state while writing a lot of the book, but I also admit that my characters, in turn, enchanted me. This is the moment when I might explain that the novel’s origins began when I started to hear voices, but that’s another story for another time.

This writer has experienced her most enchanted states at our cabin in the north woods where much of The Conditions of Love was written. You might say that in solitude and stillness, my apprehension of and connection to the invisible world ripened. The wind spoke to me, the pines spoke to me, the sun-diamonds on the lake and the slap of water against the shore worked their magic. At other times while writing the novel, I took myself to foreign towns where I’d rent a bungalow and sit myself down to write. Enchantment can occur at any time, but it does seem to appreciate an escape from the familiar.

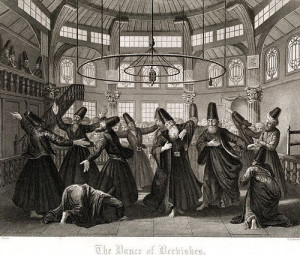

We don’t talk much about enchantment, but most of us have experienced it and still get glimpses. For example, music shares an ancient relationship to enchantment. Think: hymns, chants, rattles and drums. On a more modern note, I recently read that melody and rhythm trigger the same dopamine system in the brain that rewards food and sex. Absolutely! Who didn’t think that whirling dervishes and ecstatic dancers of every stripe were having more fun than the rest of us! It appears neuroscience has finally caught up with what the sages always knew.

There’s so much violence and terror in the world today.  “You name it, the world is aflame,” said Gary Samore, a former national-security aide in the Obama Administration, to New York Times reporter Peter Baker. I wonder where we can find an antidote to the dread and doom? Where can we look for relief? Couldn’t an engagement with enchantment, that is, to stand in wonder at what does exist, open worlds of possibility and present a wedge of light in the darkness?

“You name it, the world is aflame,” said Gary Samore, a former national-security aide in the Obama Administration, to New York Times reporter Peter Baker. I wonder where we can find an antidote to the dread and doom? Where can we look for relief? Couldn’t an engagement with enchantment, that is, to stand in wonder at what does exist, open worlds of possibility and present a wedge of light in the darkness?

Here’s a very brief list of fiction writers who play with enchantment in their work. Poets need their own list.

Suggested reading:

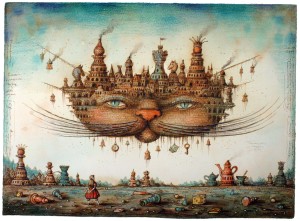

Lewis Carroll: The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland

Italo Calvino: Invisible Cities

Steven Millhauser: Little Kingdoms; The Knife Thrower and Other Stories

Louise Erdrich: The Plague of Doves

Tea Olbrecht: The Tiger’s Wife

anything by Jorge Luis Borges or Edgar Allan Poe

anything by Angela Carter