One of the ways we learn to know ourselves is through language. Philosophy, psychiatry and psychology, linguistics and neuroscience – each investigates the relationship between language, thought, and self-identity. Some experts argue we can’t have language without first having a thought (I think, therefore I speak or write); other experts espouse the opposite: our language constrains what we’re able to think (the Hopis, for instance, were said to not have a way to express “the day after tomorrow”).

Forgetting the scholarly debates, common sense and experience tell us that thought, language, and knowing ourselves are intricately bound.

In my earlier blogs, I’ve written about the relationship between empathy and literature (See, for instance, “How Facing Our “Shadow” Can Release Us from Scapegoating”), how literature offers a portal into lives like or unlike our own. When we read or listen to fiction or poetry, we are essentially opening our hearts and minds to universal human experiences, stories told in the voice of others that expand our capacity to better know ourselves more fully. Alaa Al Aswany, the celebrated Egyptian author and activist involved in the 2011 Tahrir Square demonstrations, writes: “Literature is not a tool of judgment – it’s a tool for human understanding.”

In my earlier blogs, I’ve written about the relationship between empathy and literature (See, for instance, “How Facing Our “Shadow” Can Release Us from Scapegoating”), how literature offers a portal into lives like or unlike our own. When we read or listen to fiction or poetry, we are essentially opening our hearts and minds to universal human experiences, stories told in the voice of others that expand our capacity to better know ourselves more fully. Alaa Al Aswany, the celebrated Egyptian author and activist involved in the 2011 Tahrir Square demonstrations, writes: “Literature is not a tool of judgment – it’s a tool for human understanding.”

While language is a key element to self-identity, the paths to self-knowledge are various.

The spiritual route directs us to prayer, meditation, fasting, chanting, retreat or working among the destitute. Psychology offers an extensive menu of options: dreamwork; cognitive behavior therapy; mindfulness-based therapy; psychodynamic therapy; and the vast world of psychopharmacology.

Via Creativa is another more rarely considered route to self-knowledge. It is the inspired creation of theologian Matthew Fox, a former Dominican priest in the Roman Catholic Church and an admirer of medieval mystics and visionaries such as Hildegard of Bingen, Saint Francis of Assisi, and Meister Eckhart.

Via Creativa is another more rarely considered route to self-knowledge. It is the inspired creation of theologian Matthew Fox, a former Dominican priest in the Roman Catholic Church and an admirer of medieval mystics and visionaries such as Hildegard of Bingen, Saint Francis of Assisi, and Meister Eckhart.

Via Creativa, the path of creativity, is part of Fox’s Creation Spirituality, a four-fold path to awareness of self through awareness of the divine.

Via Positiva is the path of awe, beauty and joy, Via Negativa, the path of darkness, pain and suffering that are inherent in a spiritual journey, and Via Creativa, according to Fox, is the path of generativity and creativity, the path of poetry, art, and creative work.

The fourth path, Via Transformativa, is the way of transformation made possible through practice and awareness of the first three paths.

We gain self-knowledge through the words and sentences we choose to describe ourselves, but it’s also true that we can learn about ourselves through the words of others. Poems, like stories, offer an avenue into self-discovery.

In the spirit of Via Creativa, and with attention to language as a way of knowing, and to continue my own exploration of the relationship between mothers and daughters (See “Mothers, Witches, and the Power of Archetypes” and “Our Mothers, Ourselves: the Search for the Whole Story”), I offer several poems by women about their mothers. Here we find ourselves in their hidden moments of praise or sorrow, anger or joy.

The first poem is by Leslie Ullman, the author of four poetry collections, most recently Progress on the Subject of Immensity, and of a hybrid collection of craft essays, poems, and writing exercises titled Library of Small Happiness. She teaches in the low-residency MFA Program at Vermont College of the Fine Arts and lives in Taos, New Mexico.

The first poem is by Leslie Ullman, the author of four poetry collections, most recently Progress on the Subject of Immensity, and of a hybrid collection of craft essays, poems, and writing exercises titled Library of Small Happiness. She teaches in the low-residency MFA Program at Vermont College of the Fine Arts and lives in Taos, New Mexico.

Being Not Her

I did not know how to flirt

or sew or navigate my days without

a trace of self-doubt. My demeanor

was serious (You need to have

a light touch with boys. And remember

to make them feel important). She

stayed married until death did them part

after 69 years. I married twice and did not

change my name. She adored men. I

was afraid men would distract me. Men

adored her. I wanted them to adore me

and also to leave me alone. I wrote poems

she didn’t understand and stopped reading

as our lives deepened into their separate modes.

I resented my native suburb, her comfort zone—

but oh, the lilacs and lily-of-the-valley every

spring, their perfumes thrilling, filling me

with the promise of being grown up, even after

I knew better. Every year I miss them

as I add annuals to my own high-desert square

of decent soil, guided by her words: don’t be afraid

to experiment. You’ll remember what thrives.

When I asked Leslie to tell me a little about the origin of this poem she wrote me the following, in which she stresses how time and maturity mellowed her relationship to her mother. She speaks for many women who awaken later in life to a new understanding of their mothers.

“I had been thinking about what it’s like to be an elder myself, with a mother still in the world. I also had been marveling at how lucky I was to have outgrown my resentment of feeling controlled by a well-intentioned but willful, self-confident, and often tactless mother, to emerge into a friendship with her. It occurred to me that many daughters don’t have enough time with their mothers for this to happen – they’re stuck with old business, which may be as much a matter of perception as of anything else, and never have time to feel liked and appreciated by their mothers, or to like their mothers back. I also think this has to do with outgrowing one’s need for a mother’s approval, which can take a long time!”

Audre Lorde described herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who dedicated her life and her work to fighting injustice. In the following poem, she speaks of a painful childhood, her need for motherly love from a light-skinned mother who disdained her dark-skinned daughter. The poet calls on the spirit of her personal mother and the Great Mother to hear her need and to heal her.

Audre Lorde described herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who dedicated her life and her work to fighting injustice. In the following poem, she speaks of a painful childhood, her need for motherly love from a light-skinned mother who disdained her dark-skinned daughter. The poet calls on the spirit of her personal mother and the Great Mother to hear her need and to heal her.

My mother had two faces and a frying pot

where she cooked up her daughters

into girls

before she fixed our dinner.

My mother had two faces

and a broken pot

where she hid out a perfect daughter

who was not me

I am the sun and moon and forever hungry

for her eyes.

I bear two women upon my back

one dark and rich and hidden

in the ivory hungers of the other

mother

pale as a witch

yet steady and familiar

brings me bread and terror

in my sleep

her breasts are huge exciting anchors

in the midnight storm.

All this has been

before

in my mother’s bed

time has no sense

I have no brothers

and my sisters are cruel.

Mother I need

mother I need

mother I need your blackness now

as the august earth needs rain.

I am

the sun and moon and forever hungry

the sharpened edge

where day and night shall meet

and not be

one.

Alice Friman’s poem “Snake Hill” also speaks with urgency to a mother who is frail and dying. It recounts a childhood experience but now the roles are reversed: the child is mother to the feeble mother. Remorse and longing underpin the words that speak of how difficult it is to let go of a beloved no matter what our age.

Alice Friman’s poem “Snake Hill” also speaks with urgency to a mother who is frail and dying. It recounts a childhood experience but now the roles are reversed: the child is mother to the feeble mother. Remorse and longing underpin the words that speak of how difficult it is to let go of a beloved no matter what our age.

Snake Hill

to my mother

We are on the final avenue.

Hush now. What’s to speak?

Soon we’ll go down Snake Hill,

cobblestones and weedy lots.

Will you sing to me as we go?

In the toy store window, the guitar

I wept my heart out for,

the rubber bands still stretched with song.

We can buy it now. There’s no end

to what we can afford.

I’m lying.

It’s gone. The window.

The store. The whole corner where

Frank’s Market spilled crates out to the curb.

But I’m still there, wailing,

and you pleading reason to I want

I want. (What early prick of glass

keeps that vein open still?)

Snake Hill is steep.

The lyrics overflow the hour. After,

it will take me years to turn

and face that climb alone,

each paving stone weed-wet with song

catching at my throat, my throat

filled with you.

Only the child

at the top of the hill

can yank me up again—by the heart’s cord

running down the roof of her mouth

to the cut bands of the throat—the child

who has no other choice, having nothing left

from that corner to retrieve.

Alice offered some background about her poem, which appears in her book Inverted Fire:

“About why I wrote the piece, well I was very close to my mother, and the thought of what was to come haunted me. What I’m remembering – Snake hill, Frank’s market, the toy store window where being three, I wailed for what I could not have, it being the heart of the depression and she surely didn’t have the necessary twenty-three cents – are scenes from my childhood in Washington Heights, New York City.”

Alice Friman’s seventh collection of poetry, Blood Weather, will be published by LSU Press in 2019. She’s the winner of a Pushcart Prize and is included in Best American Poetry. She lives in Milledgeville, Georgia, where she was poet-in-residence at Georgia College.

Naomi Shihab Nye is a child of shared cultures, the daughter of an American mother and a father who was a Palestinian refugee. The American Poetry Foundation says of her poetry: “Nye’s experience of both cultural difference and different cultures has influenced much of her work. Known for poetry that lends a fresh perspective to ordinary events, people, and objects, Nye has said that, for her, “the primary source of poetry has always been local life, random characters met on the streets, our own ancestry sifting down to us through small essential daily tasks.” “Voices” appears in Tender Spots: Selected Poems.

Naomi Shihab Nye is a child of shared cultures, the daughter of an American mother and a father who was a Palestinian refugee. The American Poetry Foundation says of her poetry: “Nye’s experience of both cultural difference and different cultures has influenced much of her work. Known for poetry that lends a fresh perspective to ordinary events, people, and objects, Nye has said that, for her, “the primary source of poetry has always been local life, random characters met on the streets, our own ancestry sifting down to us through small essential daily tasks.” “Voices” appears in Tender Spots: Selected Poems.

Voices

I will never taste cantaloupe

without tasting the summers

you peeled for me and placed

face-up on my china breakfast plate.

You wore tightly laced shoes

and smelled like the roses in your yard.

I buried my face in your

soft petaled cheek.

How could I know you carried

a deep well of tears?

I thought grandmas were as calm

as their stoves.

How could I know your voice

had been pushed down hard inside you

like a plug?

You stood back in a crowd

but your garden flourished and answered

your hands. Sometimes I think of the land

you loved, gone to seed now,

gone to someone else’s name,

and I want to walk among silent women

scattering light. Like a debt I owe

my grandma. To lift whatever cloud it is

made them believe speaking is for others.

As once we removed treasures from your

sock drawer and held them one-by-one,

ocean shell, Chinese button, against the sky.

Memory, longing, and a deep recognition of what is carried from one generation to the next informs how each of these poets explores motherhood. And these I’ve shared are just a sliver of the rich trove of discoveries poets are engaged in. You may enjoy “Daughters in Poetry,” an essay and tour by Eavan Boland at The Academy of American Poets or you may prefer to explore the exemplary work of the many individual poets available at the Poetry Foundation.

In her book, Of Woman Born, poet and essayist Adrienne Rich, wrote: “Probably there is nothing in human nature more resonant with charges then the flow of energy between two biologically alike bodies, one of which has lain in amniotic bliss inside the other, one which has labored to give birth to the other. The material here is for the deepest intimacy and the most powerful estrangement.”

As you sit with these poems, consider what one event crystalizes your relationship to your mother. What emotions does it bring up? What have you never said to her that you now wish to say? There. That’s your material!

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

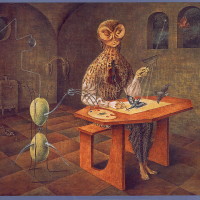

Top image, “Mother and Daughter,” courtesy of Colorado mixed media artist, Saundra Lane Galloway. Saundralane.com