There was an old woman who lived in a shoe.

She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do.

She gave them some broth without any bread;

And whipped them all soundly and put them to bed.

How entrancing those nonsensical rhymes were to us as children, the chant more compelling than the meaning. As adults, however, we hear the verses with more mature ears and try to divine their symbolic meaning.

What about the mother portrayed in the Mother Goose rhyme? Her origins may be traced to Queen Caroline, wife of King George II, and her large brood, or the rhyme may refer to an ancient superstition linking fertility to shoes. But even if the poor, old, overburdened woman is a stand-in for a real person, she also represents the archetype of a harried worn-out mother, her children starving for attention and love. As an archetypal image of an unfit mother, she reflects a set of conditions that exist across time and continents, as does the depiction of her childrens’ desperate situation.

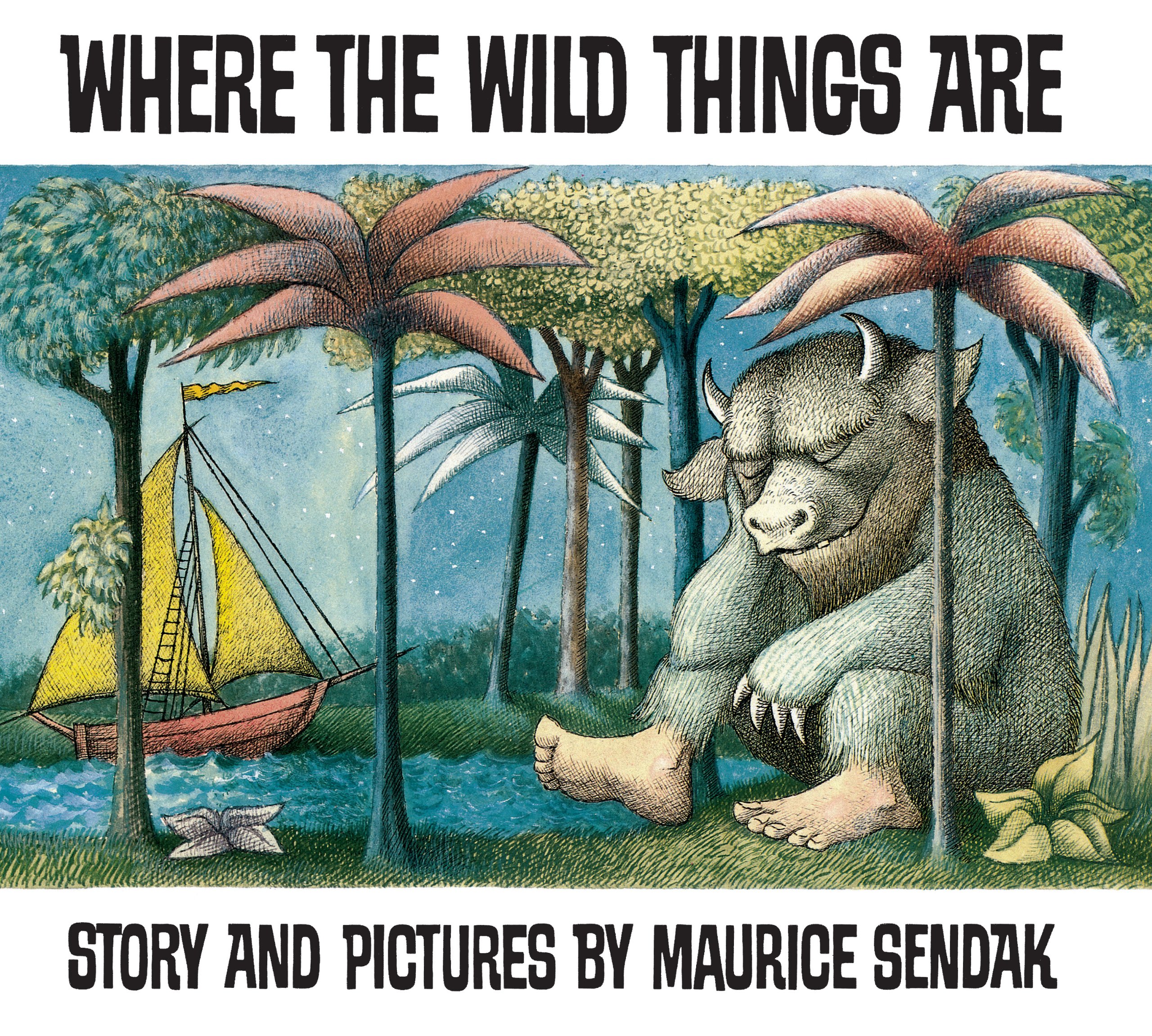

Cultural images of a range of mothers and mothering abound. Consider the haranguing critical mother-in-the-sky in “Oedipus Wrecks,” Woody Allen’s segment of the film New York Stories. A female deity with tight curls and a kvetching voice, Sadie Millstein is the intrusive and unescapable mother from Hell, a Medea in her own right. On the opposite end of the spectrum are the all-good mothers, Margaret March, “Marmee,” in Little Women, or the self-sacrificing mother in Fanny Hurst’s novel Imitation of Life. Dickens gives us the negligent Mrs. Copperfield, and Mrs. Jellby in Bleak House. Jane Austen’s Mrs. Bennet is a loving mother but a social climbing fool. As we age, witches and hags, fairy godmothers and cuddling mamas tramp through our dreams.

Cultural images of a range of mothers and mothering abound. Consider the haranguing critical mother-in-the-sky in “Oedipus Wrecks,” Woody Allen’s segment of the film New York Stories. A female deity with tight curls and a kvetching voice, Sadie Millstein is the intrusive and unescapable mother from Hell, a Medea in her own right. On the opposite end of the spectrum are the all-good mothers, Margaret March, “Marmee,” in Little Women, or the self-sacrificing mother in Fanny Hurst’s novel Imitation of Life. Dickens gives us the negligent Mrs. Copperfield, and Mrs. Jellby in Bleak House. Jane Austen’s Mrs. Bennet is a loving mother but a social climbing fool. As we age, witches and hags, fairy godmothers and cuddling mamas tramp through our dreams.

We tell stories about our own mothers—to ourselves, to friends, to our partners and our therapists, but are the stories we repeat the whole picture? Whether our mothers were vicious or supportive, praising or blaming; whether we consider them a benevolent or malicious force, our mothers were our first love. As our earliest and most primary relationship, the way we attach to our mothers in infancy will shape how we respond to love the rest of our lives.

Understanding our mothers as complex figures free daughters to accept their undiscovered or disowned parts. The often painful quest to sort through the past and to explore who our mothers were beyond the stories we’ve told ourselves can satisfy an unconscious yearning for wholeness within ourselves.

In her book, In Her Image: The Unhealed Daughter’s Search for Her Mother, Jungian analyst Kathie Carlson invites the reader to dive deeper into the complex relationship between mothers and daughters and to consider that relationship in a fuller context that goes beyond personal experience. Carlson differentiates three points of view from which we can understand our mothers: the child’s, the feminist, the archetypal.

In her book, In Her Image: The Unhealed Daughter’s Search for Her Mother, Jungian analyst Kathie Carlson invites the reader to dive deeper into the complex relationship between mothers and daughters and to consider that relationship in a fuller context that goes beyond personal experience. Carlson differentiates three points of view from which we can understand our mothers: the child’s, the feminist, the archetypal.

Carlson begins with the woman who raised us, our personal mother: “The primary relationship between women is the relationship of mother and daughter. This relationship is the birthplace of a woman’s ego identity, her sense of security in the world, her feeling about herself, her body, and other women.” Mother is The Source. She is our container, our protectress, the vital entity in which we grow, through which we are born, and upon which our survival depends. (I am speaking here, too, of transgendered women, of men who take on the primary caretaker role of “mother”). As mother, she holds our life and death in her hands. A problem arises, however, when an adult daughter continues to view her mother from the child’s perspective, when she evaluates the mother in terms of how she affects her (the child), expecting the mother to be all things “supportive, nurturing, unselfish, and infinitely caring,” qualities that suppose a super-human flawless being.

Carlson suggests the child’s point of view is egocentric and limited, but necessarily so when we are infants and children. As infants, we need to establish a bond with an all-powerful presence who will appear when we wail in hunger and who can fulfill our basic needs. The degree to which we have missed out on quality mothering is mirrored in the physical and emotional distress that may emerge as we develop. In extreme cases of negligence or abuse, children are vulnerable to a condition called failure to thrive (FTT).

A problem arises when we carry the developmental needs and expectations of childhood into adulthood and continue to suffer the rage or depression engendered by early deprivation. “Many of us,” Carlson writes, “have not had even adequate mothering, much less the ideal; many of our mothers have been too depleted themselves. We end up disappointed in our mothers, hurt, angry, blaming, needy, raging, yet unable to let go of our need for them. We feel starved emotionally…We feel terrified of becoming like our mothers…”

A problem arises when we carry the developmental needs and expectations of childhood into adulthood and continue to suffer the rage or depression engendered by early deprivation. “Many of us,” Carlson writes, “have not had even adequate mothering, much less the ideal; many of our mothers have been too depleted themselves. We end up disappointed in our mothers, hurt, angry, blaming, needy, raging, yet unable to let go of our need for them. We feel starved emotionally…We feel terrified of becoming like our mothers…”

As Carlson notes, many carry within us this unhealed child and an attendant sense of unworthiness, which affects our other relationships. Healing the core woundedness, she explains, involves a deeper and more comprehensive view of our mothers, one that does not negate the child’s view but includes looking at our mothers as women with their own histories, needs, and temperaments as well as expanding our understanding of our mother as part of a transpersonal order.

If the first perspective from which we see our mothers is the child’s egocentric view, the second perspective is what Carlson calls a feminist perspective, and what I call a woman-to-woman perspective. From this viewpoint, our mothers are products of their histories, their biology, their culture, their temperament and genes. Seeing our mothers through this lens allows us to replace the ideal projected image with a more realistic and empathetic knowledge of who our mother really is. This is not to say an abused, neglected, or mistreated daughter denies or excuses wrongful mothering, only that by seeing her mother as a full human being for whom she can feel sympathy, the daughter is more able to separate from her mother and to feel compassion for her own deeply held pain.

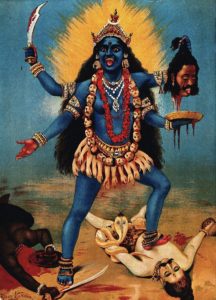

The third perspective Carlson introduces in her book is the experience of the archetypal or transpersonal mother who “comes through” to us in dreams and religious symbols, in Mother Nature, and in experiences that help us reframe our emotional connection to our personal mothers. A way to understand how archetypes work in our lives is to imagine that all aspects of all mothers are contained in the collective archetype of Mother. She who is named the Shekhinah, the feminine complement to God; the Great Huntress; the Queen of Heaven; Hera; Astarte; Sophia; the Madonna; Kali; Lilith.

If, for instance, we have felt abandoned by our personal mothers or have felt her meanness and betrayal, we can look to the ancient stories and symbols that depict both the light and dark sides of the Mother. Knowing this, we are more able to relativize our personal experience. We do not deny or excuse the pain or the perpetrators of that pain, but we can feel less isolated, less bitter and resentful knowing our pain is part of the continuum of the human condition.

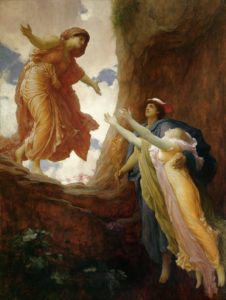

As an interesting experiment, we can gather tales that speak to us of our experiences as the daughter of our mother. Do we identify with the abandoned and orphaned Little Match Girl, or the under-appreciated object of jealousy, Cinderella? Perhaps we feel closer to Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, who is separated from her mother by Hades, and dragged into the underworld. Perhaps there are more contemporary stories that resonate with ours. In any case, find stories that reflect your own experience and think how the story might be told first from the daughter’s point of view, and then differently, from the mother’s point of view. Imagine hearing Mrs. Portnoy’s worried voice narrating the trouble she sees ahead for little Alexander! What might you learn about yourself if you heard your own mother’s whole story?

As an interesting experiment, we can gather tales that speak to us of our experiences as the daughter of our mother. Do we identify with the abandoned and orphaned Little Match Girl, or the under-appreciated object of jealousy, Cinderella? Perhaps we feel closer to Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, who is separated from her mother by Hades, and dragged into the underworld. Perhaps there are more contemporary stories that resonate with ours. In any case, find stories that reflect your own experience and think how the story might be told first from the daughter’s point of view, and then differently, from the mother’s point of view. Imagine hearing Mrs. Portnoy’s worried voice narrating the trouble she sees ahead for little Alexander! What might you learn about yourself if you heard your own mother’s whole story?

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at