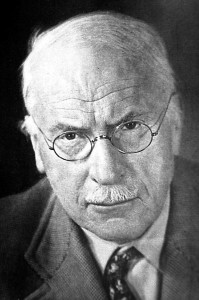

When we scapegoat, we project what is dark, shameful and denied about ourselves onto others. This “shadow” side of our personality, as Carl Jung called it, represents hidden or wounded aspects of ourselves, “the thing a person has no wish to be,” (Collected Works, Vol. 16) and acts in a complementary and often compensatory manner to our persona, or public mask, “what oneself as well as others think one is.” (Collected Works, Vol. 9).

When we scapegoat, we project what is dark, shameful and denied about ourselves onto others. This “shadow” side of our personality, as Carl Jung called it, represents hidden or wounded aspects of ourselves, “the thing a person has no wish to be,” (Collected Works, Vol. 16) and acts in a complementary and often compensatory manner to our persona, or public mask, “what oneself as well as others think one is.” (Collected Works, Vol. 9).

The desire to disown despised parts of oneself has ancient and universal roots. In his compelling study of comparative religion and myths, The Golden Bough, social anthropologist Sir James Frazer devotes several chapters to documenting the variety of forms scapegoating has taken through the ages: undesired attributes or illnesses being magically transferred onto defeated enemies, living animals, or in some instances, interred inside objects such as trees. The contaminated “thing” was thought to be detachable and disposable, as when nail or skin parings of a sick man might be stuffed into a hole in the ground.

The word “scapegoat” originated in the Bible’s Book of Leviticus. In the ancient Hebrew tradition, a high priest, acting in the service of Yahweh, offered the blood of a slaughtered goat to purify the tabernacle. The transgressions of the community were projected onto a second goat that was then sent out to wander the desert. Though banished into exile, the goat itself was not considered evil, but rather was a sacred vehicle used for atonement, thus ridding the community of its negative elements and reconnecting the tribe with the Divine. While we no longer believe animal sacrifice can purify our communities, the practice of scapegoating continues, although in a much corrupted form.

The word “scapegoat” originated in the Bible’s Book of Leviticus. In the ancient Hebrew tradition, a high priest, acting in the service of Yahweh, offered the blood of a slaughtered goat to purify the tabernacle. The transgressions of the community were projected onto a second goat that was then sent out to wander the desert. Though banished into exile, the goat itself was not considered evil, but rather was a sacred vehicle used for atonement, thus ridding the community of its negative elements and reconnecting the tribe with the Divine. While we no longer believe animal sacrifice can purify our communities, the practice of scapegoating continues, although in a much corrupted form.

Sylvia Brinton Perera in her book, The Scapegoat Complex, writes: “We apply the term “scapegoat” to individuals and groups who are accused of causing misfortune. This serves to relieve others, the scapegoaters, of their own responsibilities, and to strengthen the scapegoaters sense of power and righteousness.” One has only to read the world news to recognize that our impulse to transfer rejected and hated parts of the self onto others is everywhere destructively alive. Ostracism, bullying, name-calling, banishment from community all serve a false dichotomy between “us” and “them.” In one example, we may experience aggressive impulses, feel guilty about them, develop a persona of accommodation and passivity while our unconscious and unprocessed anger wears the face of “the enemy.”

Perera continues, “Scapegoating…means finding the one or ones who can be identified with evil or wrong-doing, blamed for it, and cast out of the community in order to leave the remaining members with a feeling of guiltlessness.” By demonizing other racial, ethnic and gender groups for their troubles, scapegoaters are able to maintain their own “innocence” and remain blind to the moral imperatives facing them. In totalitarian regimes, in some theocracies, and even in our own country, conspiracy theorists not only target individuals and other countries as scapegoats, but project blame for the society’s difficulties onto the disciplines of science, art, and the humanities.

Sadly, the tyrannical force of scapegoating, with its cruel thrusts of accusatory judgments, can also erupt in our own backyards. This closer-to-home variety of scapegoating is especially important to note since we may find ourselves condemning bullies and world leaders while denying our own inclination to split off and project fears and anxieties onto our intimates and neighbors. The scapegoat-victim in families is often the “black sheep,” the child who, like the ancient sacrificial goat, serves the miserable role of carrying the unconscious shadow parts of her parents. These children may present with psychological problems and exhibit addictive or self-destructive behavior, but a deeper look into family dynamics points to a lack of awareness of the influence of parents’ unconscious feelings.

Carl Jung believed that scapegoating revealed something fundamental about our psyche. He maintained that we all have a “shadow” side to our personality. As he wrote in Archetype and the Collective Unconscious, “The shadow personifies everything that the subject refuses to acknowledge about himself.” Our shadow aspects cause us anguish, and much of our mental energy is enlisted in the denial of our perceived imperfections, but we cannot see our shadow aspects except through projection. In Alchemical Studies, Jung wrote, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making darkness conscious.” This is where art and literature can awaken us to our own blind spots and human frailties.

Carl Jung believed that scapegoating revealed something fundamental about our psyche. He maintained that we all have a “shadow” side to our personality. As he wrote in Archetype and the Collective Unconscious, “The shadow personifies everything that the subject refuses to acknowledge about himself.” Our shadow aspects cause us anguish, and much of our mental energy is enlisted in the denial of our perceived imperfections, but we cannot see our shadow aspects except through projection. In Alchemical Studies, Jung wrote, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making darkness conscious.” This is where art and literature can awaken us to our own blind spots and human frailties.

The sorrow of the scapegoated child is palpably conveyed in John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden through the character of Cal, the no-good son, who carries the weight of his father’s unconscious anger and disappointment. So, too, does the character Biff in Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman suffer for his father’s moral blindness. The evil daughter in the film The Bad Seed and the horrifying children in The Village of the Damned illustrate how unconscious shadow aspects can manifest as the ungovernable and unconscionable impulses we assign to psychopaths and aliens. And who can forget the tragic fate of the deformed and scapegoated Quasimodo in Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame? The list continues. Tom Robinson, the black man on trial in To Kill A Mockingbird is the victim of racial scapegoating. Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter is victimized for her gender and sexuality.

David Grossman, an Israeli author concerned with the brutalization of minds and hearts of people in countries perpetually at war, writes about the results of scapegoating in Writing in the Dark. He calls this radical denial of feelings “a shrinking of our soul’s surface.” Concerning the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he writes, “Given a situation so frightening, so deceptive, and so complicated—both morally and practically—we feel it may be better not to think or know…Better not to feel too much until the crisis ends.” The dulling of feeling, the indifference to suffering—one’s own or that of others—hopelessness and despair, these are what we pay for demonizing the other while failing to accept our own darker emotions. Grossman concludes that self-anesthesia solves nothing. The suffering continues, goes underground, explodes in acts of violence against the self or innocent victims.

“It is everybody’s allotted fate to become conscious of and learn to deal with this shadow . . . The world will never reach a state of order until this truth is generally recognized.”—Carl Jung, Collected Works, Volume 10, par. 455

To own one’s rage, aggression, and greed is a lifelong and arduous process that requires a willingness to live beyond binary, black-and-white thinking and to embrace our complicated and messy humanity. Here we might learn a lesson from Maurice Sendak’s beloved picture book, Where the Wild Things Are, a delightful and wondrous graphic map to the terrors and ultimate acceptance of the monsters within. Young Max, the book’s protagonist, is furious at his mother. Sent to bed without dinner, he is soon conveyed into a dreamscape of seemingly terrible monsters—And the wild things roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth. Their insistent plea is to be seen and recognized, a transformational act which turns them into buddies. This turning toward and not away from what is fearsome in ourselves is a deep lesson in self-knowledge and integrity, a counterpoint to the drive to scapegoat. It echoes the poet Rilke’s famous line from Letters to A Young Poet, “Perhaps everything terrible is in its deepest being something helpless that wants help from us.”

To own one’s rage, aggression, and greed is a lifelong and arduous process that requires a willingness to live beyond binary, black-and-white thinking and to embrace our complicated and messy humanity. Here we might learn a lesson from Maurice Sendak’s beloved picture book, Where the Wild Things Are, a delightful and wondrous graphic map to the terrors and ultimate acceptance of the monsters within. Young Max, the book’s protagonist, is furious at his mother. Sent to bed without dinner, he is soon conveyed into a dreamscape of seemingly terrible monsters—And the wild things roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth. Their insistent plea is to be seen and recognized, a transformational act which turns them into buddies. This turning toward and not away from what is fearsome in ourselves is a deep lesson in self-knowledge and integrity, a counterpoint to the drive to scapegoat. It echoes the poet Rilke’s famous line from Letters to A Young Poet, “Perhaps everything terrible is in its deepest being something helpless that wants help from us.”

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

If you enjoyed this post, you may like to read these related posts: “Soulwork: The Role Archetypes Play in Jungian Analysis,” “Altruism, the Helper Archetype and Knowing Your Intention,” and “Mothers, Witches, and the Power of Archetypes.”