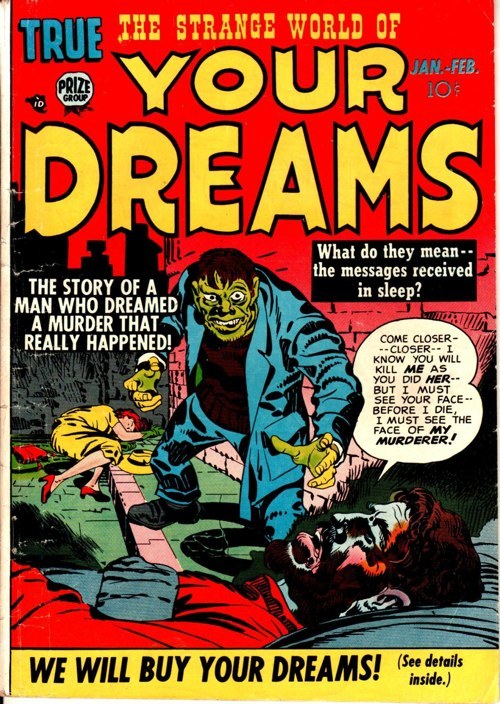

Exploring Jung’s revolutionary idea of dreams as compensation

One of the physiological marvels of our species, which we share with animals, is a process called homeostasis. The word means “steady state” and refers to how our bodies adjust to internal and external changes to maintain a dynamic equilibrium of our systems. According to the Britannica Encyclopedia, homeostasis is “any self-regulatory process by which biological systems tend to maintain stability while adjusting to conditions that are optimal for survival.”

To adjust to external temperatures or to fight an infection, our bodies shiver to raise our internal temperature or sweat to lower it. When we ingest sugar, our pancreas secretes insulin to help us balance glucose in our blood. Our blood vessels contract or expand to direct blood flow as needed. None of these functions are under our conscious control any more than sneezing or itching.

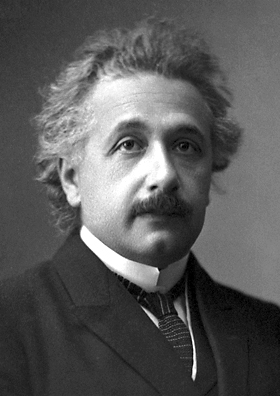

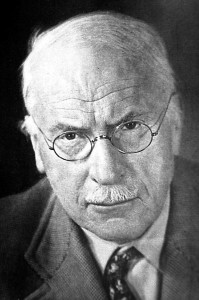

One of the great Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s most significant concepts was that our psyche seeks this same kind of balance between our consciousness and the unconscious and that our brain uses dreams as the psyche’s self-regulatory system. He proposed that one of the functions of dreams is to compensate for our conscious thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs by providing a different point of view through dream imagery.

Based on his work as a psychiatrist at the Burghöizli Hospital in Zurich, and analytic sessions with his private clients, he concluded that by presenting repressed and archaic archetypal material from the unconscious, dreams offered a remedy to the one-sidedness of ego-consciousness. This led to his concept of dreams as compensation.

Based on his work as a psychiatrist at the Burghöizli Hospital in Zurich, and analytic sessions with his private clients, he concluded that by presenting repressed and archaic archetypal material from the unconscious, dreams offered a remedy to the one-sidedness of ego-consciousness. This led to his concept of dreams as compensation.

In The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, Jung wrote:

The unconscious content contrasts strikingly with the conscious material, particularly when the conscious attitude tends too exclusively in a direction that would threaten the vital needs of the individual. The more one-sided his conscious attitude is, and the further it deviates from the optimum, the greater becomes the possibility that vivid dreams with a strongly contrasting but purposive content will appear as an expression of the self-regulation of the psyche.1

Consider this simple example of the compensatory function of dreams and how it might benefit the dreamer: a client carries a low opinion of herself and struggles with depression. During this period, she dreams of a grammar-school teacher from her past who praised her creativity and determination. This memory has been excluded from her conscious mind but returns in dreams to remind the dreamer of her forgotten potential buried under the depression. After working with these dreams in therapeutic sessions, she finds new energy to enroll in painting classes and reunites with her creative energies.

In his wonderfully engaging new book The Four Pillars of Jungian Psychoanalysis, the distinguished Jungian analyst, Dr. Murray Stein, includes a chapter on dreams that clarifies Jung’s notion of dreams as compensation. He writes:

The unconscious is another realm with a life of its own, and often it runs quite contrary to what is going on in the world of consciousness. When a person is sleeping, another type of thinking is taking place that is different from waking thought. Dreams can give us important information about what is going on within ourselves and about possible developments for the future. But beyond that, and more important for the outcome of analysis, is that dreams build the way to psychological wholeness.2

Working with dreams and using dream interpretation to decode their symbolic content can lead to the transcendence of repressed material and the renewal of the self. As Dr. Stein suggests, we might ask ourselves, “Why this dream at this time?” What the unconscious brings forward, he further suggests, depends on the present state of one’s consciousness. Viewing a dream as compensatory medicine, we then might ask ourselves: what wound or trauma is the unconscious aiming to heal?

Several months ago, during a difficult time of personal questioning, I had a dream in which a salamander became a healing talisman I was to wear around my neck. When I awoke, the oppressive feelings that had been haunting me were gone. Salamanders are not creatures I commonly encounter in my daily life, nor do I think about them, and yet a numinous and magical salamander appeared in my dream. The dream, in turn, changed my relationship with my feelings. Later, when I looked up the symbolic meaning of salamander, I was amazed to discover salamanders have long been associated with totems of transformation.

Several months ago, during a difficult time of personal questioning, I had a dream in which a salamander became a healing talisman I was to wear around my neck. When I awoke, the oppressive feelings that had been haunting me were gone. Salamanders are not creatures I commonly encounter in my daily life, nor do I think about them, and yet a numinous and magical salamander appeared in my dream. The dream, in turn, changed my relationship with my feelings. Later, when I looked up the symbolic meaning of salamander, I was amazed to discover salamanders have long been associated with totems of transformation.

The nature and function of dreams continue to provoke spiritual, scientific, and psychological debate. However, in honoring their symbolic meaning and potentially healing function, we resource the hidden treasures in our depths that can alter our relationship to our inner world and restore us to a more balanced life.

What images, symbols, or dream-stories are knocking on the door of your consciousness?

References

1Jung, Carl. The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, Collected Works, Volume 8, p 346. Princeton University Press. 1970

2Stein, Murray. The Four Pillars of Jungian Psychoanalysis, Chiron Press. 2022

You may also be interested in my other recent blog posts about dreams

“Dream Incubation: Solving Problems in Your Sleep”

“Dream Disturbances: The Healing Function of Bad Dreams”

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

![“Atomic Skull” mixed media (8’ x 6’) by Korean War veteran Jim Leedy (2000). After swimming in a lake filled with rotting corpses in 1952, Leedy had nightmares for decades. “The making of that [‘The Earth Lies Screaming’] wall and the skull head emancipated me from my dreams and I never had a bad dream after that.” Atomic Skull by Jim Leedy for Empathy post](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/atomic-skull-leedy-large.jpg)