A number of years ago, a friend who is familiar with my tendency to worry brought me a present, a book called The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook. I remember tearing off the gift wrap and looking quizzically at the title. Huh? But as I thumbed through pages of advice—what to do if your finger gets caught in a deli slicer, or how to pull yourself out of quicksand, or escape a crocodile attack—I got my friend’s humorous point: our imagination is a wondrous mechanism, but sometimes it works overtime to spin out dreadful tales. (As an aside, his humor coincided perfectly with something one of my creative writing professors once told me: when you open the gates of imagination, there’s no predicting what will fly through!)

My friend and I shared some hardy laughs over a few of the book’s absurd entries, but inwardly I sighed in relief. On the spectrum of crazy worries, mine were not extreme. When it came to catastrophic thinking, I was obviously not alone.

My friend and I shared some hardy laughs over a few of the book’s absurd entries, but inwardly I sighed in relief. On the spectrum of crazy worries, mine were not extreme. When it came to catastrophic thinking, I was obviously not alone.

Not everything we imagine should we believe. Many of the scenarios our minds create are unlikely to befall us. Imagine being in an airplane that is experiencing turbulence. The windows rattle. A storage bin pops open. Dropping altitude, the plane pitches and shakes. Worst case scenario—you’re plummeting through space.

Maybe, but probably not. Odds are the plane will right itself, pass through the turbulence, and land safely at its destination. Air safety statistics are in our favor, but during moments of terror, we visualize the worst. Strong emotions can clog our cognitive channels. The more vivid the images and sensory experience of doom, the more likely they will lead us to a faulty conclusion about what’s occurring by out-muscling our rational brains. The fact that catastrophic imaginings can be utterly convincing doesn’t make them true.

Catastrophizing has a lot to do with our mind’s ability to produce fantastically realistic images that run like high definition movies in our heads. This can sometimes be useful. Elite athletes use visualizations to enhance performance. Olympians are not alone in mentally rehearsing record-breaking outcomes by imagining their ability for athletic perfection. Guided visualizations, imagining best outcomes, also help people get through medical procedures, addiction issues, or common fears such as anxiety about public speaking.

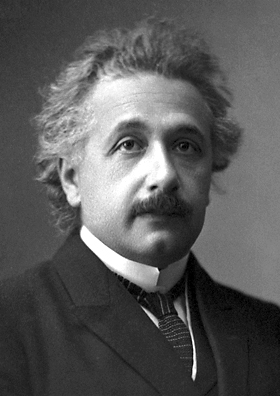

This is imagination’s marvelous capacity—to change our attitudes and behaviors. One of its main jobs is to open new doors to the possible. There is a popular quote frequently attributed to Albert Einstein: “Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere.” What he actually said was “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”—from an interview in The Saturday Evening Post in 1929. The irreverently wise Dr. Seuss put it another way, “I like nonsense; it wakes up the brain cells.”

Imagination also serves as a bridge to empathy. After all, if we can’t imagine walking in another person’s shoes, we are cut off from knowing and empathizing with their experience.

However, when imagination’s focus is catastrophe, we could say it has gone wild. In a previous blog, I’ve written about anxiety as our brain’s way of trying to protect us from real or imagined danger, part of a neural warning system whose priority is to keep us safe and alive. When we catastrophize, a part our brain is alerting us: “Get ready, here it comes.” But in this instance, the perspective is skewed. Clouded by emotion, our perceptual apparatus can’t relay the information needed to make a sound judgment. We are unable to discern that our neighbor’s fearsome snarling dog has terrible arthritis and no teeth.

Anxious thoughts can scare the bejeezus out of us, but they do not have malicious intent. And while it’s true that part of our mammalian repertoire includes a nervous system that signals us to flee or physically overcome a threat, it’s also worth considering that beyond this hard-wiring, stories of catastrophe are embedded in our literary imaginations as well.

The stories we grew up with from the Old and New Testaments are chock full of catastrophes. Floods, plagues, Satan and his evil-doing minions, transformations into pillars of salt, and of course the fiery tortures of hell all linger in our collective Western imaginations. Catastrophe also befalls Greek, Roman and Hindu heroes. In most wisdom traditions and in fairy tales, catastrophe follows disobedience, ignoring a prohibition, or transgressing against moral or traditional law.

“You may peer into any room but that room,” Bluebeard instructs his newest wife after handing her a set of keys. Do not eat the forbidden apple; do not stop to speak to the wolf on your path. By all means, do not kill your father and marry your mother. Watch out for your hubris, your pride. Do not try to imitate the gods.

“You may peer into any room but that room,” Bluebeard instructs his newest wife after handing her a set of keys. Do not eat the forbidden apple; do not stop to speak to the wolf on your path. By all means, do not kill your father and marry your mother. Watch out for your hubris, your pride. Do not try to imitate the gods.

We might wonder if some of our present-day anxieties have been handed down over generations whose guilt and fears of sin and punishment have become our own. How might our own deepest fears be a form of self-punishment, the curse of an unconscious inner demon?

Not that real catastrophes don’t happen every day. Fires, mudslides, category four hurricanes, tsunamis, school shootings, random shooters, famine, measles epidemics—the revelation of horrific incidents has increased substantially in modern times. Here, anxiety leads us between a rock and a hard place. For the sake of our survival, and the planet’s, we must stay alert and conscious of the dangers to our society; to our peril do we shrug off scientific evidence for climate change or a need to reconsider gun control laws. The melting of the polar ice cap, the ruination of coral reefs are not fairy stories or cautionary tales. Denial won’t make them go away.

One way to work with catastrophizing thoughts is what The Worst-Case Scenario Handbook aims to do: give the reader clear, concrete, and specific instructions on how to work through a particular terrifying event. Facing down a raging lion on the savannah? Here’s what you do. Less exotic worries afflict most of us. What if that mole turns out to be cancer? What if my partner’s shirt reeks of an unfamiliar perfume? Here’s where we can get help from our reasoning mind. In the face of threatening thoughts, we can engage our smart frontal lobe. Is this scary thought likely to be true? If the answer is yes, what logical and concrete action can we take to elevate the situation? We can try to observe our scary thoughts with detached curiosity. We can ask ourselves: Is this worry part of a familiar pattern that has derailed me before? If the answer is yes, try to remember the first time you had the thought and the circumstances that provoked it. In doing so, you may gain insight into the very origins of your concerns.

The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook is now in its fourth edition. I take this as a sign that anxiety and catastrophic fears are not going away any time soon. Humor can blast through fear in surprising ways. It might be worth buying a copy of Handbook, if only to get a good laugh at the madly funny things we come up with to scare ourselves.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

![“Atomic Skull” mixed media (8’ x 6’) by Korean War veteran Jim Leedy (2000). After swimming in a lake filled with rotting corpses in 1952, Leedy had nightmares for decades. “The making of that [‘The Earth Lies Screaming’] wall and the skull head emancipated me from my dreams and I never had a bad dream after that.” Atomic Skull by Jim Leedy for Empathy post](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/atomic-skull-leedy-large.jpg)