A Conversation with Jungian Analyst Kenneth James (Part Three)

This post continues my conversation with esteemed Jungian analyst Kenneth James. In Part One, we focused on how Jungian analysis is different from conventional therapies and other analytic traditions. In Part Two, we discussed the importance of dreams in Jungian analysis. In Part Three, we turn to archetypes.

Perhaps you are wondering: Why pay attention to dreams and archetypes when our daily life seems on the verge of collapse? Stores are shuttered and bare. Some of us have lost our jobs. Some have lost our health. Many of us have lost faith in the possibility of a more just and equitable world. Isn’t turning toward our inner life rather indulgent?

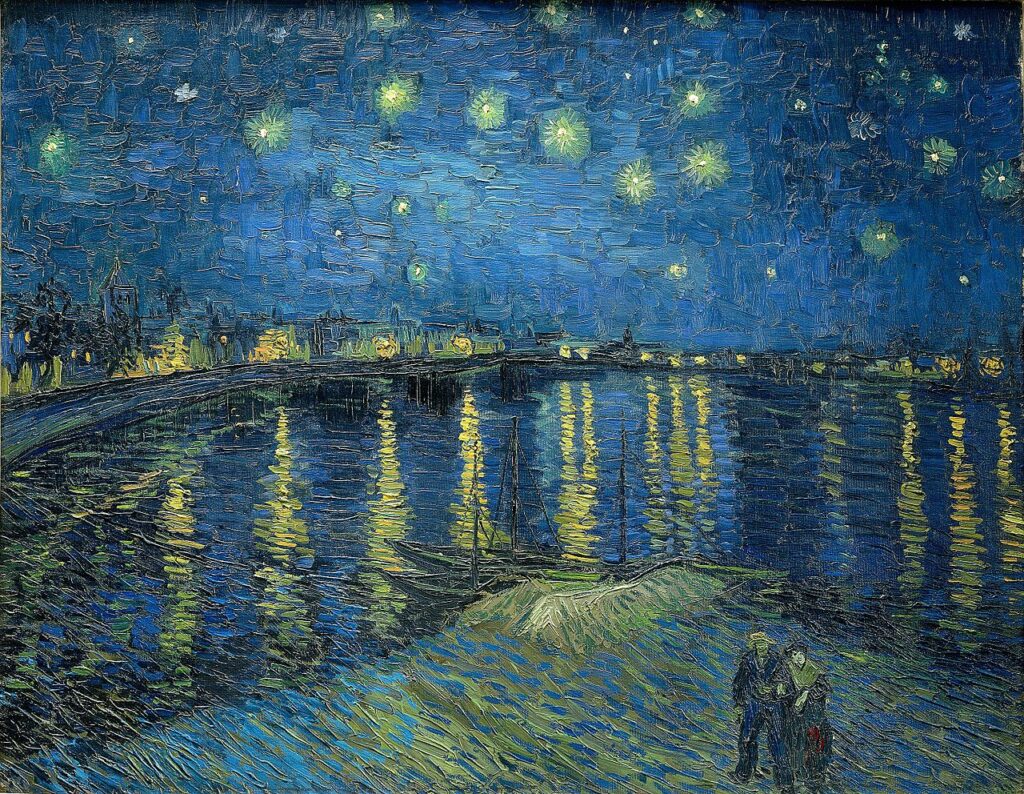

Collectively and individually, we are in a state of transformation. The future is uncertain and our energies limited. To turn inward toward our dreams is to honor life’s mysteries and place trust in a source beyond our ego’s domain. In dreams, contradictions and paradoxes abound: we can be both shattered and strong, frightened and brave. We can run from the tiger, and in the next moment, be the tiger.

Think of a dream as a portal, or a portal leading to other portals, by which we enter wildly new terrain where at any moment fresh insights might impress themselves upon us.

Kenneth James holds the rank of professor emeritus after a 33-year career as a university professor and now devotes his time as founder and director of The Soulwork Center in downtown Chicago, where he practices as a Jungian analyst.

Kenneth James holds the rank of professor emeritus after a 33-year career as a university professor and now devotes his time as founder and director of The Soulwork Center in downtown Chicago, where he practices as a Jungian analyst.

Dale Kushner: What is the definition of “archetype?”

Kenneth James: Archetypes are best conceived as organizing principles that are part of the human psyche simply by virtue of a person’s existence in the world of space and time. Archetypes in themselves are a priori givens and are not derived from an individual’s particular experiences in their lifetime. The images associated with particular archetypes, including visual images, myths, legends, scriptures, and any other artifacts of human presence on earth, are created through individual experience and cultural transmission. Thus, the images I associate with, for example, physical love and sexuality, will be informed by the mythological image of Aphrodite, or Venus in Roman mythology, because given my age, society, culture, and educational experiences, her mythic image emerges as dominant for me. The archetype-in-itself has no image, but images quickly attach to the archetypes. As I go through life, the archetype of physical love and sexuality is also amplified by my own personal experiences of physical intimacy, the attractions I feel, the images I encounter from art, cinema and literature, and even myths I encounter from other cultures and religions, either through education. From a Jungian perspective, experiences are not provided for us by the environment; rather experiences are constructed through an interaction between the archetypal ground and the particular day-to-day stimuli that we encounter.

D.K.: What archetypes have the COVID-19 virus constellated and how might they appear in a person’s psyche?

K.J.: The COVID-19 virus is an interesting phenomenon. All of the depictions of the virus offered in the media show a spherical center with projections coming off the surface perpendicularly. In Analytical Psychology, the sphere, or any mandala (circular) shape, is usually thought of as an emblem of the Self. Jung wrote that at times when an individual is experiencing significant chaotic emotional challenges in daily life, a round image may emerge in dreams or daydreams. Jung felt that the multiple axes of symmetry found in circles and spheres, all arranged around a center point, were an attempt on the part of the psyche to provide an image of order and stability in the face of psychic chaos. How curious then that the image we are given of the COVID-19 virus should be, of all things, a mandala.

In my practice, dream images of the virus itself has not figured significantly, but the effects of the pandemic have appeared abundantly in dreams. Fear of being overtaken by a flood; concerns about whether the foundation of a high-rise building will be able to withstand the impact of runaway hurricane winds; jogging in territory familiar to the dreamer, but in spite of attempting to run “full out,” the dreamer feels like she is running through a lake of molasses—all of these have been dream images which, upon investigation between analyst and analysand, point to the anxiety, fear and confusion surrounding psyche’s attempt to come to terms with this exceptional time.

In my practice, dream images of the virus itself has not figured significantly, but the effects of the pandemic have appeared abundantly in dreams. Fear of being overtaken by a flood; concerns about whether the foundation of a high-rise building will be able to withstand the impact of runaway hurricane winds; jogging in territory familiar to the dreamer, but in spite of attempting to run “full out,” the dreamer feels like she is running through a lake of molasses—all of these have been dream images which, upon investigation between analyst and analysand, point to the anxiety, fear and confusion surrounding psyche’s attempt to come to terms with this exceptional time.

Perhaps the images that medical science has given us of the virus itself, the sphere with perpendicular protuberances, is a way for the Self to remind us that wholeness lies at the core of every experience. Even in the global chaos that we are now experiencing, the fundamental processes of life are in order and can be considered not only as destructive but also as providing an opportunity to form a new relationship to the world. Just as death and birth are characteristic of every cell of our bodies throughout our lifetimes, so may we be being reminded to find the wholeness amidst the chaos, move toward that, and begin to organize our experiences in a more coherent, symmetrical and balanced manner.

D.K.: How do archetypes figure in Jung’s view of the personal and collective unconscious?

K.J.: The archetypes are the organizing principles which constitute the collective unconscious. It is because of the archetypes that the collective unconscious exhibits such a high level of organizational structure, and why more or less direct expressions of the collective unconscious patterns such as are found in myth, fairy tales, religion, and literature are also highly organized with a rich web of connections among all the archetypal images in any given system. With this as a foundation, the personal unconscious also can achieve a similar architecture. Whereas the collective unconscious is populated with contents (the archetypes) which were never part of the space/time experience of any particular individual, the personal unconscious is composed of material that was at one time part of day-to-day experience. Aspects of this personal material, which may be thought of as residue from encounters in the so-called outer world, finds its way to the personal unconscious so that it may be processed by the ego and ultimately integrated into our understanding of who we are. Most of us discover the contents of the collective unconscious through intense consideration of personal experiences, including dreams, daydreams, projection, displacement, somatization, parapraxis, and synchronicity. These “disclosures” from the unconscious, if considered respectfully as sources of valuable insight into personal suffering, show the intimate connection Jung believed operated between personal and collective aspects of the unconscious.

K.J.: The archetypes are the organizing principles which constitute the collective unconscious. It is because of the archetypes that the collective unconscious exhibits such a high level of organizational structure, and why more or less direct expressions of the collective unconscious patterns such as are found in myth, fairy tales, religion, and literature are also highly organized with a rich web of connections among all the archetypal images in any given system. With this as a foundation, the personal unconscious also can achieve a similar architecture. Whereas the collective unconscious is populated with contents (the archetypes) which were never part of the space/time experience of any particular individual, the personal unconscious is composed of material that was at one time part of day-to-day experience. Aspects of this personal material, which may be thought of as residue from encounters in the so-called outer world, finds its way to the personal unconscious so that it may be processed by the ego and ultimately integrated into our understanding of who we are. Most of us discover the contents of the collective unconscious through intense consideration of personal experiences, including dreams, daydreams, projection, displacement, somatization, parapraxis, and synchronicity. These “disclosures” from the unconscious, if considered respectfully as sources of valuable insight into personal suffering, show the intimate connection Jung believed operated between personal and collective aspects of the unconscious.

D.K.: Does analysis involve trying to identify which archetype mostly closely “fits” an analysand?

K.J.: Absolutely not! To do such a thing is completely ego-based, which is not the Jungian way. Finding a fit can be seen as a sort of parlor-game approach to the collective unconscious made popular nowadays in a variety of ways, from decks of cards depicting subsets of “the archetypes,” to disjointed considerations of individual mythic characters who may be seen as motifs that may, at times, bear a strong resemblance to some aspect of an individual’s life. If we try to identify “the” archetype which “fits” an analysand, we would be doing the opposite of what analysis seeks to accomplish. Such a static understanding of the archetypes ignores completely the vast web of interconnection among all of the archetypes of the collective unconscious.

The meaning of analysis is “loosening.” Therefore, one goal of analysis is loosening up the unconscious identification with particular episodes in one’s personal history. Analysis can also shed light when we feel stuck in patterns of relationship to our experience which, upon deeper consideration, can be seen to exemplify particular archetypal motifs. This loosening comes about by exploring the connections among archetypes and finding ways of encouraging psychic movement that can free us from the possession we can experience at the archetypal level. It is perhaps more correct to say that we come to analysis already unconsciously identified not only with aspects of our personal history but also with a fixed subset of the characters and situations from the archetypal ground. Analytic work seeks to free us from those unconscious identifications. We are always far more than we can ever believe ourselves to be, and analysis makes this abundantly clear. Throughout our lifetime, we will experience many parts of the archetypal ground, and believing there is one particular node or element of that ground that “fits” me is an egoic attempt to control the dynamic nature of the human person. It is this dynamism that analysis seeks to support and encourage.

This closes my three-part conversation with Jungian analyst Kenneth James. I described my own experience with Jungian training in “Treating Patients or Creating Characters,” and my decision to choose to become a novelist rather than a therapist. No surprise that readers sometimes comment on the Jungian themes in my novel, The Conditions of Love. I’m happy to participate virtually in reading group discussions of my work, and the themes I explore, whether Jung, dreams, archetypes, resilience, mother/daughter relationships, intergenerational trauma, etc. You can find information on how to reach me on my Contact page.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on my blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of my blog posts for Psychology Today at

An analogy might be how scar tissue forms around surgery sites or broken bones. On the one hand, the new tough tissue may seem like a new kind of strength, but in reality, the adaptation limits the flow of life. The growth of scar tissue restricts the flow of blood and creates stiffness and loss of flexibility, although it does bring protection from further injury. This process mirrors narcissistic adaptations in which one’s character can become constricted, stiff, and rote, distorting the shape of one’s life. A “narcissistic feed,” (the need to be admired and feel superior) dominates the interpersonal relationships in the narcissist’s world. The individual unconsciously and part consciously uses relationships to affirm the value of the grandiose self, this false self.

An analogy might be how scar tissue forms around surgery sites or broken bones. On the one hand, the new tough tissue may seem like a new kind of strength, but in reality, the adaptation limits the flow of life. The growth of scar tissue restricts the flow of blood and creates stiffness and loss of flexibility, although it does bring protection from further injury. This process mirrors narcissistic adaptations in which one’s character can become constricted, stiff, and rote, distorting the shape of one’s life. A “narcissistic feed,” (the need to be admired and feel superior) dominates the interpersonal relationships in the narcissist’s world. The individual unconsciously and part consciously uses relationships to affirm the value of the grandiose self, this false self.