Facing an unknown future is on all our minds. I’m reminded of the adage: “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.” Recently, awaiting medical results for someone I love, I was swamped by feelings of uncertainty and apprehension—the devil I didn’t know. Waiting and wondering felt more charged than learning the results, good or not so good. (Thank goodness the outcome was positive!) Once I had the facts, I trusted my warrior self would step forward and cope with whatever the future held. Perhaps this resonates with you? My experience inspired this blog to enlarge our understanding of uncertainty and offer some tools to ease distress.

Uncertainty. Why does this word make us shudder? One reason is that we are living in a time of accelerated and radical change. When our personal and communal lives feel at risk, when uncertainty is a frequent visitor, anxiety is likely to follow. As Dr. Mazen Kheirbek, an associate professor in UC San Francisco’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, tells us, “Uncertainty is not knowing what is going to happen.”[i] The combination of uncertainty and threat generates anxiety.

Evolution has wired us to adapt to uncertainty but what in our brains activates the sense of being uncertain? Researchers at the University of Cambridge in the UK have been investigating this in humans and developed tests that demonstrated that the neuromodulator noradrenaline is the key chemical that underpins behavioral and computational responses to uncertainty. Their research focused on a small area in the brain stem, the locus coeruleus, that regulates noradrenaline and enhances sensory learning.[ii] Another set of researchers at University College London created human experiments that found two other neuromodulators, acetylcholine and dopamine, which affect uncertainty.[iii] Understanding of how these neurotransmitters work is evolving.

Our brains are agile and can sometimes assess an uncertain situation by remembering and comparing it to a past experience—Oh, when my partner goes quiet like this, I know they are about to explode; I’d better change the subject—but for other situations we can’t rely on past experience. They require quick thinking and a new approach to uncertainty. Understanding how our brains adapt to volatile and changing situations will be ever more important as food and water scarcity, climate disasters, wars, and migrating populations challenge us at an unprecedented pace.

Our brains are agile and can sometimes assess an uncertain situation by remembering and comparing it to a past experience—Oh, when my partner goes quiet like this, I know they are about to explode; I’d better change the subject—but for other situations we can’t rely on past experience. They require quick thinking and a new approach to uncertainty. Understanding how our brains adapt to volatile and changing situations will be ever more important as food and water scarcity, climate disasters, wars, and migrating populations challenge us at an unprecedented pace.

When we feel uncertain, our brains are trying to figure out how to balance risk and loss. Our capacity to decide is hindered by doubt, anxiety, and avoidance of a perceived threat. Anyone who has waited for medical results for themselves or loved ones might feel, as I did, that when we know what we are facing, even when it’s difficult news, we can make a plan and take action. We are no longer holding our breath.

According to Dr. Aoiefe O’ Donovan, an associate professor of psychiatry at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences who studies the ways psychological stress can lead to mental disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): “Uncertainty means ambiguity, which means that we have to expend effort in trying to predict what will happen in addition to preparing to deal with all of the different outcomes.”[iv] The stress of uncertainty, especially when prolonged, is among the most insidious stressors we experience as human beings, said O’Donovan. But, when faced with these feelings, it can help us to recognize that gnawing uncertainty is the amplification of a cognitive mechanism that’s essential to our survival.

At her Life Events Lab at the University of California, Riverside, Dr. Kate Sweeny focuses her research on “high stakes waiting.” “[Psychologists] don’t know that much about waiting and uncertainty,” according to Sweeny. In 2019, her lab looked into whether engaging in “flow,” a state of complete immersion in one activity, helped people during anxiety-provoking periods. They found that engaging in “flow” boosts a person’s sense of well-being and makes the waiting period easier.[v]

To answer questions about how we function, science researchers probe the structure and mechanisms of our brains. Spiritual traditions address the nature of being from a different perspective. Their inquiry is not centered on neuroscience or molecular biology but on how to live a full and joyous life that includes difficult or unpleasant experiences. These traditions help us recognize that uncertainty can have a positive side. Uncertainty can be an aid to curiosity, creativity, and inner peace. When we are overwhelmed with feelings of uncertainty and dread as we face an unpredictable future, we can expand our perspective and consider reframing our belief: what we habitually regard as a distressing state can be a benevolent friend.

In the Buddhist practices, uncertainty is a certainty and considered a wise teacher.[vi] The wisdom of uncertainty is that it teaches us that the nature of reality is impermanence; all things arise and disappear. All things are transient. Flux and change animate the universe and are not under our control. No matter how careful we are crossing a street, we cannot control the maniac driver who sweeps around the corner and hits us. No matter how much we exercise or eat broccoli, we cannot control the time or manner of our death. These are uncomfortable truths. Most of us have not been schooled in trusting the unknown and surrendering to life as it presents itself in the moment. This is the challenge of “calm abiding” as we meet uncertainty.

The benefits of yoga, breathing exercises, and meditation to settle a jittery nervous system are well known. From a place of stillness, we become aware of a larger presence within us that observes life as it ebbs and flows without constricting into fear. We simply observe and note this is the way life is—unpredictable.

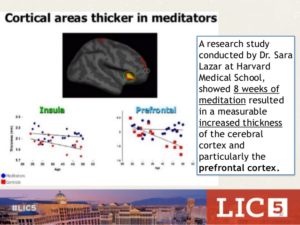

A specific Buddhist practice that helps ground us during times of uncertainty is Metta. Considered a concentration meditation, it is also called a loving-kindness practice. When we focus on a repetition of phrases, or a mantra, or the sensations of breathing, the frontal part of our brain responsible for attention is activated and the areas responsible for excitatory emotional response stop overfiring. The body relaxes. The Greater Good Center, Science-based Practices for a Meaningful Life at the University of California, Berkeley has a seven-minute Loving-Kindness-Meditation that can get you started.

A specific Buddhist practice that helps ground us during times of uncertainty is Metta. Considered a concentration meditation, it is also called a loving-kindness practice. When we focus on a repetition of phrases, or a mantra, or the sensations of breathing, the frontal part of our brain responsible for attention is activated and the areas responsible for excitatory emotional response stop overfiring. The body relaxes. The Greater Good Center, Science-based Practices for a Meaningful Life at the University of California, Berkeley has a seven-minute Loving-Kindness-Meditation that can get you started.

Can you think of a time when uncertainty sparked a sense of aliveness and adventure in you? Or perhaps an insight arose during a period of waiting and not knowing? Uncertainty begs for a playful attitude toward life, invites the inner child to step forward without fear of success or failure. Uncertainty calls on us to do something that may be difficult but rewarding: to embrace unpredictability as a constant companion

[i] Reynolds, Brandon R., “There’s a Lot of Uncertainty Right Now — This is What Science Says That Does to Our Minds, Bodies,” UCSF News, November 1, 2020.

[ii] Lawson, Rebecca P., et al., “The Computational, Pharmacological, and Physiological Determinants of Sensory Learning under Uncertainty,” Current Biology, January 11, 2021.

[iii] Marshall, Louise, et al., “Pharmacological Fingerprints of Contextual Uncertainty,” PLOS Biology, November 15, 2016.

[iv] Reynolds, Brandon R. Ibid.

[v] Rankin, K., Walsh, L., and Sweeny, K., “A Better Distraction: Exploring the Benefits of Flow During Uncertain Waiting Periods,” Emotion, Vol 19, No. 5, 2019.

[vi] Rinpoche, Anam Thubten, “The Wisdom of Uncertainty,” Buddhist Door, April 17, 2020.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

If you found this post interesting, you may also want to read “What Ancient Traditions Can Teach about Coping with Change,” “Can Mindfulness Bring About Real Change?” and “Waiting: a Source of Anxiety or Opportunity for Discovery?”

Keep up with everything Dale is doing by subscribing to her newsletter.