![“Atomic Skull” mixed media (8’ x 6’) by Korean War veteran Jim Leedy (2000). After swimming in a lake filled with rotting corpses in 1952, Leedy had nightmares for decades. “The making of that [‘The Earth Lies Screaming’] wall and the skull head emancipated me from my dreams and I never had a bad dream after that.” Atomic Skull by Jim Leedy for Empathy post](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/atomic-skull-leedy-large.jpg)

Sometimes a book we’ve had for years falls off the shelf at just the right moment. I read James Hillman’s book, A Terrible Love of War, in 2004 when it was first published as a response to 9/11. In this, his 28th book, Hillman sought to examine the archetypal roots of our “madness for battle,” the “myths, philosophy, and theology of war’s deepest mind.” He was moved to write it because of what he found missing in other books about war. He rejected, for instance, Susan Sontag’s concluding assertion in Regarding the Pain of Others:

“We can’t imagine how dreadful, how terrifying war is and how normal it becomes. Can’t understand. Can’t imagine. That’s what every soldier, every journalist and aid worker and independent observer who has put in time under fire and had the luck to elude the death that struck down others nearby stubbornly feels. And they are right.”

“She is wrong,” Hillman counters, “If we want war’s horror to be abated so that life may go on, it is necessary to understand and imagine.”

In an interview years after he was secretary of defense, Robert McNamara stated that the catastrophe of the war in Vietnam over which he presided pointed to “a failure of imagination.” Years later, comparing our unpreparedness for the attack on Pearl Harbor with that on the Twin Towers, National Security Agency director Michael Hayden famously said, “perhaps it was more a failure of imagination this time than last.”

For both men, a failure of imagination implies a failure to apprehend a reality that is present but hidden or incomprehensible, which is to say, that we do not apprehend we cannot comprehend. In order to understand and respond to something, we must first be able to see it.

Muriel Rukeyser came to a similar conclusion in 1949. In The Life of Poetry, she writes: “We are a people tending toward democracy at the level of hope; on another level, the economy of the nation, the empire of business within the republic, both include in their basic premise the concept of perpetual warfare. It is the history of the idea of war that is beneath our other histories…But around and under and above it…is the history of possibility.”

Muriel Rukeyser came to a similar conclusion in 1949. In The Life of Poetry, she writes: “We are a people tending toward democracy at the level of hope; on another level, the economy of the nation, the empire of business within the republic, both include in their basic premise the concept of perpetual warfare. It is the history of the idea of war that is beneath our other histories…But around and under and above it…is the history of possibility.”

It is this sense of hidden possibility, of renewed inspiration that now urgently calls for my attention. A failure of imagination implies a failure of empathy, our ability to stand in another’s shoes. Empathy and imagination seem to many the weak sisters of rigorous rational thinking, and yet, might they be an avenue to creative change? This strikes me as critical for us now as individuals and as a society. Can a Clinton voter imagine the anxieties of a Trump voter? Can a Trump voter imagine the fears of a Muslim?

We live at a time of enormous turmoil and transition, a time when re-apprehending and re-comprehending how we view the world is crucial, and re-examining the governing modes of how we make meaning timely.

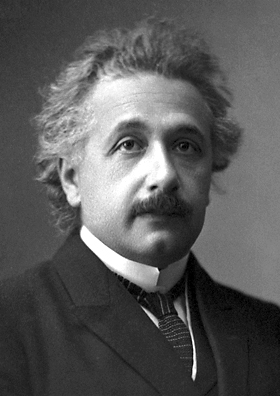

Einstein said we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. He also said the true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination. We often forget that each of us has our own ready source of imagination in our production of dreams. Each of us possesses a variety of marvelous, fantastic, even weird images and scenarios remembered from our nightly vision. Here, in our own production studios, we might discover creative insights that have the potential for personal and cultural transformation.

Einstein said we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. He also said the true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination. We often forget that each of us has our own ready source of imagination in our production of dreams. Each of us possesses a variety of marvelous, fantastic, even weird images and scenarios remembered from our nightly vision. Here, in our own production studios, we might discover creative insights that have the potential for personal and cultural transformation.

Listen to Einstein describe a dream he had as a teen:

“I was sledding with my friends at night. I started to slide down the hill but my sled started going faster and faster. I was going so fast that I realized I was approaching the speed of light. I looked up at that point and I saw the stars. They were being refracted into colors I had never seen before. I was filled with a sense of awe. I understood in some way that I was looking at the most important meaning in my life.”

Later in life, Einstein reflected, “I knew I had to understand that dream and you could say, and I would say, that my entire scientific career has been a meditation on my dream.” This dream led to him figuring out the mathematics of relativity theory.

Freud and Jung have argued that our dream images are not random and without meaning; with scrutiny, we can find that they contain a secret language of symbolic representation. These representations are both individual and personal, arising out of our unique experiences, but connected, especially in Jung’s interpretation, to a collective unconscious.

Structurally, dreams unfold as series of sights, sounds, and feelings that do not necessarily make logical sense. The interpretation of dreams relies upon their metaphoric and associative logic, the juxtaposition of unlikely or unrelated elements that can evoke surprising meanings. This is how many poems “work.” Take these lines from “Blue Mountain,” a poem by Roberta Hill Whiteman.

“Crickets whir a rough sun into haze.”

And “I sweep and sweep the broken days to echoes.”

To parse these lines would be to destroy their music and cadence and beauty, but we get what she means! To quote Rukeyser again: “A poem is not its words or its images, any more than a symphony is its notes or a river its drops of water…” The work a poem does, she writes, is to transfer human energy, “and I think human energy may be defined as consciousness, the capacity to make change in existing conditions.”

Poetry and dreams originate in that part of our psyche involved in our archetypal roots and mythic imagination. Einstein is only one example of how the geniuses of science and industry – and artists – respond to the world and its problems with the force of their imaginations, by “thinking outside the box.”

This is the route of mystery and surprise, of new conjunctions and startling awarenesses. As André Breton wrote in his Surrealist Manifesto, “I believe in the future resolution of these two states – outwardly so contradictory – which are dream and reality, into a sort of absolute reality, a surreality…”

Freud and the Surrealist artists he inspired looked for ways to expose the deeper substratum of psyche by freeing oneself of the ego’s conscious control. The use of drugs helped, as did alcohol. Automatic or spontaneous writing, collage, assembling unlikely elements into a painting freed artists from the constraints of tradition and conventional imagery. These methods of accessing the unconscious continue to be popular today. Writing workshops, workshops on trauma and addiction often use uncensored journal writing as a means to reach into dissociated aspects of self.

Becoming conscious is a lifelong task. Our dreams beg to be brought into the daylight world, to be honored, to be understood. And perhaps one of us will find within our dreams the insight or idea that might generate the transformation in empathy and imagination that James Hillman seeks – and which would benefit all of us.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at