An Interview with Trauma Therapist Brad Kammer – Part Two of Two

In Part One of my interview with trauma expert Brad Kammer, LMFT, currently on the faculty of the NARM Training Institute, we discussed how Brad and his colleagues distinguish between PTSD and complex PTSD. In Part Two, we explore how NARM’s NeuroAffective Relational Model addresses the impact of adverse childhood experiences and complex trauma. Brad and Dr. Laurence Heller outline the therapeutic framework of NARM in their new book, The Practical Guide for Healing Developmental Trauma: Using the NeuroAffective Relational Model to Address Adverse Childhood Experiences and Resolve Complex Trauma.

(Note: This is the second of a two-part interview)

You are currently on the faculty of the NARM Training Institute. What does NARM stand for? What is your working definition of trauma?

NARM stands for the NeuroAffective Relational Model, which is a model designed by my long-time mentor Dr. Laurence Heller, to address the impact of adverse childhood experiences and complex trauma. In NARM, we recognize that in most cases we cannot change the traumas we experience. But, we can change the ways we have adapted in order to survive these traumas.

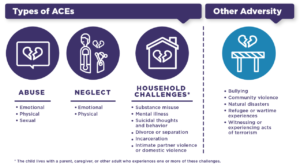

We use a developmental framework that describes five Adaptive Survival Styles which are ways we learned to adapt to attachment and environmental failures early in life. These styles form the blueprint for our adult personalities. We focus on five specific developmental stages early in childhood when the Self is just being shaped, and the ways that attachment and other environmental failures impact healthy development in each of these stages (which we are learning so much about through the Adverse Childhood Experiences research). The way that our brain and bodies adapt to these early traumas – specifically through shame – leads to various levels of often profound Self-disorganization and creates various symptoms, disorders, and syndromes.

We use a developmental framework that describes five Adaptive Survival Styles which are ways we learned to adapt to attachment and environmental failures early in life. These styles form the blueprint for our adult personalities. We focus on five specific developmental stages early in childhood when the Self is just being shaped, and the ways that attachment and other environmental failures impact healthy development in each of these stages (which we are learning so much about through the Adverse Childhood Experiences research). The way that our brain and bodies adapt to these early traumas – specifically through shame – leads to various levels of often profound Self-disorganization and creates various symptoms, disorders, and syndromes.

In Part One of our interview, you identified the important differences between Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex-PTSD. How might the treatment for each differ?

I am biased as to how I’m going to answer this question since I have been a somatic psychotherapist and trainer now for over two decades. I believe that any form of trauma healing must involve the body. Many of my colleagues have been pushing back against the more prominent “evidence-based approaches” that are usually derivatives of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and which demonstrate questionable long-term efficacy. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, continues to be a best-seller ten years after it was first published. Many people intuitively, and experientially, know that talking and thinking about our issues only take us so far. To make true and lasting change, they have to shift deeper internal patterns. This is where somatic approaches come in.

I have practiced Somatic Experiencing for over twenty years now and I find it to be the most effective model out there for PTSD. As I continued to seek models that worked more specifically with attachment, emotional, and relational trauma, I found NARM, which I believe is the most effective model out there for treating C-PTSD.

Please tell us what you mean by a person having “agency.” Why is it a game-changer?

The simplest way to define how we use the concept of Self-Agency is to highlight the various ways that individuals organize and relate to life experiences. Agency is a by-product of secure child development where a child progressively experiences themselves more as actors in their life than simply passive conduits for life experience. Other models may refer to related concepts such as Self-Activation, Self-Actualization, or Self-Realization.

When a child has experienced developmental trauma, they experience everything as just happening to them. They feel helpless to change not only their external conditions but also how they feel internally. Children may grow up feeling out-of-control (i.e., lack of impulse control), reactive (i.e., affect dysregulation), fragmented (i.e., dissociative self-states), and fragile (i.e., decreased sense of resiliency). Their lives are significantly impaired by their inner sense that they cannot self-activate, let alone change the way they feel or how they relate to the world.

NARM is grounded in an inquiry process that explores Self-Organization – how clients are organizing their internal worlds, and then relating to both their inner and outer experiences, in ways that either support connection and health or lead to disconnection and disease.

For example, your client shares a story about their experience at work last week where they were walking in the hallway and said “hello” to a colleague they were passing, and the colleague didn’t say hello back. Immediately, your client started feeling worthless, unliked, and lonely, and then started telling themselves that “I’m stupid and no one will ever like me.” They use this experience to justify why they withdraw from social interactions and experience social anxiety and depression. However, they later found out that their colleague had just received a text from a family member of a sudden loss in their family, had been in a state of shock, and not even heard your client say hello. Your client describes shaming themselves for having such a strong reaction, saying that “I’m stupid for telling myself that I’m stupid based on this situation.” This cycle of shaming oneself for shaming oneself can go on and on.

For example, your client shares a story about their experience at work last week where they were walking in the hallway and said “hello” to a colleague they were passing, and the colleague didn’t say hello back. Immediately, your client started feeling worthless, unliked, and lonely, and then started telling themselves that “I’m stupid and no one will ever like me.” They use this experience to justify why they withdraw from social interactions and experience social anxiety and depression. However, they later found out that their colleague had just received a text from a family member of a sudden loss in their family, had been in a state of shock, and not even heard your client say hello. Your client describes shaming themselves for having such a strong reaction, saying that “I’m stupid for telling myself that I’m stupid based on this situation.” This cycle of shaming oneself for shaming oneself can go on and on.

As we help clients begin to gain greater awareness of the unconscious and often automatic ways they are organizing their inner reality and relating to themselves and the world through self-shame, self-rejection, and self-hatred, they begin to experience more possibilities for organizing and relating to themselves differently. This is not just a cognitive process. It entails working psychobiologically to shift long-standing personality patterns that keep shame-based identifications intact.

Collective and intergenerational trauma are vast and necessary subjects worthy of discussion. Individuals can’t change their ancestry, and in many cases, individuals cannot change their marginalized status or persecution within a society. Can the NARM program help people traumatized by an unchanging trauma-inducing culture?

I know from my own personal experience, as well as years of clinical experience, that NARM does impact unresolved cultural and intergenerational trauma. We focus on how clients are relating to the “unchanging trauma-inducing culture” that they are born into and are still part of. For many people, the concept of “post” in post-traumatic stress disorder doesn’t truly exist. Many people are still living within and adapting to environmental failures, including sustained oppression, violence, and dislocation. And yet despite these traumatic realities, we see individuals and communities cultivating health and well-being within. It is inspiring to watch as people stop defining themselves by how others define them and embody their own authentic humanity.

I see our modern times, at least in the U.S., as defined by a widespread failure of empathy. We care less and less about our impact on others. This leads to relationships based on objectification and systems reinforcing dehumanization. The social fabric is rapidly dissolving, leaving an epidemic of loneliness and disconnection in its wake. To counter this reaction, NARM supports the development of authentic empathy. As we help people develop an increasing capacity to relate to themselves and others through acceptance and compassion, they begin to shift their own internal objectification and experience themselves as more fully human. This increased sense of humanity allows people to begin to shift the way they are relating to their family, community, and cultural systems. So while it will likely take time, I do believe NARM can impact larger changes within society.

(Read Part One: Diagnosing and Treating PTSD and Complex PTSD: It’s Not About “What’s Wrong With You?”)

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at