Archetypes abound in fairy tales, dreams, and nightmares. What do they mean for you?

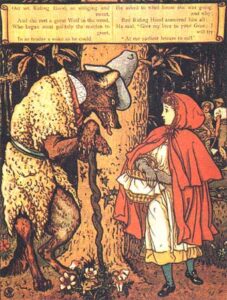

“Granny is ill,” says the mother in the fairytale “Little Red Riding Hood,” handing her daughter a basket of food for the ailing old woman. Wearing her red cloak, the little girl skips off on the path through the woods to granny’s house.

Along the way, Red Riding Hood meets a wolf. He tricks her into telling him her destination, then races off to grandmother’s and gobbles up the old woman. When Red Riding Hood arrives, the wolf is in granny’s bed wearing her nightclothes. Peeking out from beneath the covers, granny looks odd! We know the fearsome litany. What big arms you have, Grandmother! What big teeth you have! Even young listeners at this point get prickles up their spine and understand that Little Red Riding Hood must flee. But Red Riding Hood disregards the signs of danger and is soon devoured by the wolf.

In her ground-breaking book, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Women Archetype, Clarissa Pinkola Estés discusses naïve women as prey and the common fairy tale motif of the animal groom. According to Pinkola Estés, the animal groom in a tale is “a malevolent thing disguised as a benevolent thing,”1 a shadow aspect of our psyche. This type of character, wolf or human, represents an inner predator. Unrecognized, this predator can destroy us, but recognized and confronted, it can lead to an awakening of the strong Self that faces down self-destructive tendencies.

In her ground-breaking book, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Women Archetype, Clarissa Pinkola Estés discusses naïve women as prey and the common fairy tale motif of the animal groom. According to Pinkola Estés, the animal groom in a tale is “a malevolent thing disguised as a benevolent thing,”1 a shadow aspect of our psyche. This type of character, wolf or human, represents an inner predator. Unrecognized, this predator can destroy us, but recognized and confronted, it can lead to an awakening of the strong Self that faces down self-destructive tendencies.

Do not talk to strangers. Do not stray from the path. Do not open the door to strangers while we are gone. (The seven dwarves to Snow White.) Here are my keys, but never unlock that closet door. (Bluebeard’s Castle.) Fairytales pulsate with warnings. Trickster spirits—embodied by greedy witches, calculating wizards, and charming wolves—appear without fail. Trickster spirits pop into our lives as well, mercurial figures that enchant, bewitch, attract. The role of the animal groom or other destructive figures in fairy tales is to wake us up to our need to not be easily deceived or to fall into a clever trap, and to our sense of agency.

Fairy tales transport us to a timeless space in which we inhabit the domain of eternal situations—abandonment, displacement, poverty, orphanhood, war, childbirth—and meet archetypal figures, basic human types like the good daughter, the jealous sibling, the feckless father, or wise old woman that have existed across time and cultures. In dreams we may also meet archetypal figures in the shape of robbers, wicked queens, authoritative kings, kindly animals or trees, and dream figures also serve an alerting function: to awaken us to our personal unconscious, to very real situations mirrored in our psychic lives. The dream clown (archetypal figure) has the face of our first boyfriend (from personal memory) who reminds us of our current boyfriend and the uneasiness he inspires (a present situation that needs attending to). The great dream theorist and depth psychologist, Carl Jung, wrote: “The dream shows the inner truth and reality of the patient as it really is: not as I conjecture it to be, and not as he would like it to be, but as it is. “2

In dreams as in fairy tales, disturbing or brutal images capture our attention. That is their purpose, to rouse us from our habitual ways of seeing and knowing, to alarm us enough so that we sit bolt upright in bed and ask: What is going on in my life?

Jung believed that healing images lie within. Dreams, he assessed, are “small hidden doors in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul.”3 When we study our dreams, we discover the personal motifs, patterns, and themes that actively, though unconsciously, govern our lives. They are our own private fairy tales in vivid color calling to us from within. Revisiting fairy tales, especially ones we are drawn to, can shed light on our own complexes, and provide insight into the images that appear in our dreams. Do we identify with the abused Cinderella taunted by her female kin and find ourselves dreaming of a waif in rags? Are we self-sacrificing? Waiting to be transformed by a godmother? Are we the youngest son competing for our father’s attention? The tales that attract us may give us a whiff of our psyches and appear in some variation in our dreams.

Jung believed that healing images lie within. Dreams, he assessed, are “small hidden doors in the deepest and most intimate sanctum of the soul.”3 When we study our dreams, we discover the personal motifs, patterns, and themes that actively, though unconsciously, govern our lives. They are our own private fairy tales in vivid color calling to us from within. Revisiting fairy tales, especially ones we are drawn to, can shed light on our own complexes, and provide insight into the images that appear in our dreams. Do we identify with the abused Cinderella taunted by her female kin and find ourselves dreaming of a waif in rags? Are we self-sacrificing? Waiting to be transformed by a godmother? Are we the youngest son competing for our father’s attention? The tales that attract us may give us a whiff of our psyches and appear in some variation in our dreams.

If the haunting images in fairy tales stalk our sleep, and nightmares awaken us, heart thumping, the mood can sometimes carry over into the next day. Neuroscience research on nightmares and other night terrors has enlarged our understanding of what is going on in the brain. For example, researchers have found that in post-traumatic nightmares, a type of nightmare in which a real traumatic event is relived, the amygdala, the structure deep within the brain associated with fear, is overly sensitive. In other types of nightmares, researchers speculate on a neurological fear circuit involving the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex.4 Knowing the anatomical mechanism of nightmares aids clinicians in creating specific therapies to help clients work with disturbing dreams, such as rewriting or reframing a frightening dream and meditating on a positive ending.5

Let me invite you back into your dreams. If you have tried keeping a journal of dreams and stopped, begin again. If you are exploring dreamwork for the first time, consider this moment a pivotal time to turn within. Whatever you record in your dream journal has value—entire dreams in all their specificity, snippets of dreams, single images or words, associations, doodles, drawing, graphic comics—whatever comes, welcome it.

Let me invite you back into your dreams. If you have tried keeping a journal of dreams and stopped, begin again. If you are exploring dreamwork for the first time, consider this moment a pivotal time to turn within. Whatever you record in your dream journal has value—entire dreams in all their specificity, snippets of dreams, single images or words, associations, doodles, drawing, graphic comics—whatever comes, welcome it.

Record the feeling associated with the dream, both in the dream and upon awakening. If certain feelings and moods continue throughout the day, note them too.

Another way to work with dreams is to make a list of the characters in the dream including non-animate objects like a train, a suitcase, the landscape, rainclouds. Notice where there are conflicting needs and desires between the characters. The train may tell you it’s on a strict timetable. You can ask yourself: Where in my life am I on a strict timetable? How do I feel about this? Notice which characters answer readily and which are hesitant to speak or remain silent. Do these exercises several times over a week and notice what changes in the responses.

Regard whatever comes to you as the vastness of your innate wisdom asking to be heard.

Notes

1 Pinkola Estés, Clarissa, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Women Archetype

2 Jung, C. G., “The Practical Use of Dream Analysis”, Collected Works, 16: The Practice of Psychotherapy.

3 Jung, C. G., The Meaning of Psychology for Modern Man,” Collected Works,10: Civilization in Transition

4 Nielsen, Tore, “The Stress Acceleration Hypothesis of Nightmares,” Frontiers of Neurology, June 1, 2017.

5 Tousignant, O. H., Glass, D. J., Suvak, M. K., & Fireman, G. D, “Nightmares and nondisturbed dreams impact daily change in negative emotion,” APA PsycNet 2022

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at