My husband and I used to joke that together we had a complete brain. He was the scientist, a man of logical and rational thinking. I was the artist, habitual dweller in the land of reverie, seeker of mysteries and mysticism. We identified ourselves in this neatly dualist way, and neuroscience seemed to reflect our conclusions.

Betty Edwards’ book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain became a massive bestseller in the early 1980s. It popularized the idea that our brains are divided into right and left hemispheres and that each half is responsible for different and opposite functions.

Her book maintained that the right hemisphere was responsible for intuitive, impressionistic, dreamy, “feminine” functions while the left hemisphere was the more rational, here-and-now, “masculine” side of the brain.

This model replicated how my husband and I experienced the world. We perceived and evaluated situations differently. We used contrasting models to solve problems, and arrived at distinct conclusions and solutions. He relied on facts and proof; I inclined toward suppositions that questioned accepted knowledge. Cause and effect offered him clear answers. Cause and effect bored me. I liked to spin off possibilities. He liked B to always follow A. I liked to see what would happen if D followed A—and B disappeared completely! The majority of people we knew, as well as Western culture in general, shared my husband’s preferences. Some of our worst arguments resulted from the ways our apprehension of truth diverged.

Over the past decades, science has advanced our understanding of how the brain functions, and we can now say that any creative, thoughtful endeavor requires the use of our complete brain, the parts that order reality as well as the regions of emotion, memory, and ancestral wisdom. The ubiquitous yin-yang symbol above health food stores and yoga studios conveys the idea of opposition and interdependence within a container that comprises a whole.

Over the past decades, science has advanced our understanding of how the brain functions, and we can now say that any creative, thoughtful endeavor requires the use of our complete brain, the parts that order reality as well as the regions of emotion, memory, and ancestral wisdom. The ubiquitous yin-yang symbol above health food stores and yoga studios conveys the idea of opposition and interdependence within a container that comprises a whole.

Originating in China in the 3rd century BCE, the yin-yang symbol was an outgrowth of a philosophy and cosmology that saw all things existing as inseparable and contradictory. The two opposites, yin and yang, represented two opposing energies that attract and complement each other, neither pole being superior to the other. To achieve harmony in mind, body, spirit and in the greater world, the two elements must be in balance. When the two were out of balance, catastrophes such as floods, plagues, and other disasters could occur.

The balancing of yin and yang is a potent visual reminder of how differences can exist within wholeness. Looking deeply into the symbol, we can see our mind/brains as the outer circle and the black and white representing differing aspects contained within.

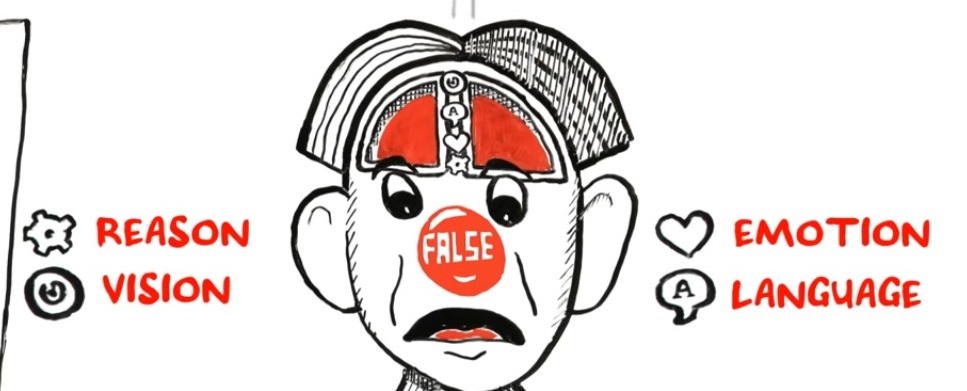

This symbology mirrors how the old reductive models of left brain/right brain have needed updating. According to more recent research, the two brain hemispheres have differences but don’t function as independently of each other as previously thought. They differ in size and shape and in the number of neurons and neural size. They differ in their sensitivity to hormones and pharmaceutical agents and other ways as well, but the most significant difference lies in the type of attention they give the world. The hemispheres house different sets of values and priorities. As he describes in The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Iain McGilchrist, a research psychiatrist, believes that over time “there has been a relentless growth of self-consciousness (left brain) and a shift away from a reliance on right brain values (more interconnected, humane and holistic.) In the new 2019 edition, he chillingly writes:

This symbology mirrors how the old reductive models of left brain/right brain have needed updating. According to more recent research, the two brain hemispheres have differences but don’t function as independently of each other as previously thought. They differ in size and shape and in the number of neurons and neural size. They differ in their sensitivity to hormones and pharmaceutical agents and other ways as well, but the most significant difference lies in the type of attention they give the world. The hemispheres house different sets of values and priorities. As he describes in The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Iain McGilchrist, a research psychiatrist, believes that over time “there has been a relentless growth of self-consciousness (left brain) and a shift away from a reliance on right brain values (more interconnected, humane and holistic.) In the new 2019 edition, he chillingly writes:

“If I am right, the story of the Western world is one of increasing left brain hemisphere domination, we would not expect insight to be the keynote. Instead, we would expect a sort of insouciant optimism, the sleepwalker whistling a happy tune as he ambles toward the abyss.”

In a dialogue with Dr. Jonathan Rowson of the RSA’s Social Brain Centre, Dr. McGilchrist explained how the brain hemispheres function differently, though each is involved in everything we do. “For each hemisphere has a quite consistent, but radically different, ‘take’ on the world. This means that, at the core of our thinking about ourselves, the world and our relationship with it, there are two incompatible but necessary views that we need to try to combine. And things go badly wrong when we do not.” Note how similar this understanding is to the ancient Taoist cosmology of the necessary balance between yin and yang.

McGilchrist and others speak of how left-brain dominance over right-brain function has led the West to drift toward a reliance on abstract, de-contextualized thinking over a more intrinsic, fluid, reflexive thought process. As a contemporary example, we could say that our reliance on and false belief in algorithms to predict human behavior in industry, government, education, and science, and our institutionalization of metrics to assess accountability come at the expense of such human values as intuition and trustworthiness.

As humans, we may applaud ourselves for being a rational, thinking species, but growing scientific knowledge reveals us to be fundamentally a social species that needs and is molded by social interaction. Our behavior may, in fact, be based less on thought than on habit.

If McGilchrist and his colleagues are correct, their research has wide relevance for how we face the existential challenges of our time. Algorithms and abstract formulas predict the impact of climate change, yet too many of our leaders ignore the lived experience of hotter summers, wetter springs, and how quickly forests and coral reefs are disappearing. Teachers have testified about the recent phenomena of students’ inability to read human faces, pay attention, and empathize. And we are just beginning to see how cell phones, the Internet, and digital devices are adversely affecting our brains.

But good news comes from studies of brain plasticity. While unhealthy trends in society do not yet seem to have altered our brains in major structural ways, the question remains: can we, as a society, reverse the negative trends already in motion? The work of Dr. Richard Davidson, a neuroscientist I have mentioned in a previous blog, “‘Let It Go!’ More Than a Song Title, the Motto for Our Age,” offers hope and concrete ways to enhance well-being through meditations aimed at coping with difficult mind states such as depression, hyperactivity, or anxiety.

Dr. Davidson offers “mindfulness meditation” as an example in The Emotional Life of Your Brain:

“The term ‘mindfulness meditation’ refers to a form of meditation during which practitioners are instructed to pay attention, on purpose and non-judgmentally. The process of learning to attend nonjudgmentally can gradually transform one’s emotional response to stimuli such that we can learn to simply observe our minds in response to stimuli that might provoke either negative or positive emotion without being swept up in these emotions. This does not mean that our emotional intensity diminishes. It simply means that our emotions do not perseverate. If we encounter an unpleasant situation, we might experience a transient increase in negative emotions but they do not persist beyond the situation.”

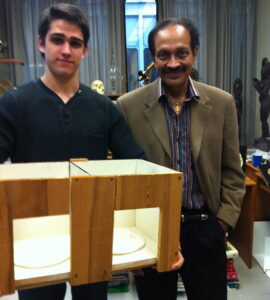

Another researcher, the psychiatrist Dr. Norman Doidge, in his book The Brain That Changes Itself, offers case histories of almost miraculous transformative cures of those afflicted with pain, cerebral palsy, phantom pain syndrome, and other brain-related maladies through the use of specific brain exercises. For instance, he describes the case in which Dr. V.S. Ramachandran successfully removed an amputee’s phantom pain by “rewiring his brain map” through the use of a “mirror box” that made the patient seem to see his phantom limb in the box before him. While the “cures” Dr. Doidge describes may be rare cases, brain plasticity is not a hoax. Moreover, this may indeed be a crucial time in the history of our species and our planet for us to embrace and consciously activate all aspects of our brains; most importantly, those previously untapped aspects that allow us to understand and access the transformative powers available within us.

Another researcher, the psychiatrist Dr. Norman Doidge, in his book The Brain That Changes Itself, offers case histories of almost miraculous transformative cures of those afflicted with pain, cerebral palsy, phantom pain syndrome, and other brain-related maladies through the use of specific brain exercises. For instance, he describes the case in which Dr. V.S. Ramachandran successfully removed an amputee’s phantom pain by “rewiring his brain map” through the use of a “mirror box” that made the patient seem to see his phantom limb in the box before him. While the “cures” Dr. Doidge describes may be rare cases, brain plasticity is not a hoax. Moreover, this may indeed be a crucial time in the history of our species and our planet for us to embrace and consciously activate all aspects of our brains; most importantly, those previously untapped aspects that allow us to understand and access the transformative powers available within us.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at