What compels us to engage despite a warning from an internal Geiger counter signaling alarm? What impels us to ignore our wisest intuitions? When is self-sacrifice disguised as altruism? Our instincts tell us a situation will not end well, and yet we feel unable to turn away from our habitual behavior.

What compels us to engage despite a warning from an internal Geiger counter signaling alarm? What impels us to ignore our wisest intuitions? When is self-sacrifice disguised as altruism? Our instincts tell us a situation will not end well, and yet we feel unable to turn away from our habitual behavior.

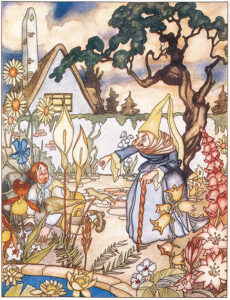

To satisfy the cravings of his pregnant wife, the distraught husband in the Grimm Brothers’ version of Rapunzel sneaks over a boundary wall to steal a special type of lettuce from a witch’s garden. He knows, as every reader of the tale knows, that stealing from a witch is risky business. His wife’s plea, however, sends him scurrying. As the story progresses, his weak judgment and transgression will be paid for by the sacrifice of his daughter, Rapunzel.

“Seeing her so pale and wretched, her husband took fright and asked: ‘What’s the matter with you, dear wife?’“She tells him she will die unless she gets that lettuce. Whatever the cost, thinks the loving husband, he will supply her with what she craves.

The husband’s dilemma has a distinctly modern resonance: I can’t let him/her/them suffer. Just this once. Next time it will be different. I did it because I love him/her/them. As social creatures, we’ve evolved to hear and respond to another’s distress. It’s our nature to empathize and want to help, but discernment is necessary to know when our help will be beneficial or result in causing further injury. The bind between refusing and acquiescing, between standing in one’s power or succumbing to the power of the emotional complex is a human conflict and afflicts not only families but also individuals caught in cycles of addiction or abuse.

The husband’s dilemma has a distinctly modern resonance: I can’t let him/her/them suffer. Just this once. Next time it will be different. I did it because I love him/her/them. As social creatures, we’ve evolved to hear and respond to another’s distress. It’s our nature to empathize and want to help, but discernment is necessary to know when our help will be beneficial or result in causing further injury. The bind between refusing and acquiescing, between standing in one’s power or succumbing to the power of the emotional complex is a human conflict and afflicts not only families but also individuals caught in cycles of addiction or abuse.

An alternative way of interpreting the husband’s role in Rapunzel is to see that making wrong choices, even seemingly disastrous choices, may be necessary for enlarging self-awareness. As any good fiction writer knows, a transgressive act starts the story rolling. A world without disastrous decisions, coercions, failures, perverse and complicated reactions does not exist. Great novels depict characters assaulted by contradictory tensions and desires. Learning occurs only when errors in judgment are made conscious and their lessons absorbed.

The idea that our deepest Self is constantly initiating us toward wholeness and psychic cohesion is one of Carl Jung’s great gifts to depth psychology. For him and his followers, every challenge has at its core a gift, a mystery to be understood. In accepting this as a guiding principle, we become seekers and move from passive victimhood to actively shaping our personal destiny. However, this can’t be accomplished until we recognize the difficulties that confront us. Like the husband, our ego and agency are vulnerable to being taken hostage by a malevolent force. In Rapunzel the witch takes this form.

The question arises: when are we being altruistic and when are our motives compromised by self-interest? How do we disentangle our desire to help from our desire to please or avoid conflict or keep the peace?

The question arises: when are we being altruistic and when are our motives compromised by self-interest? How do we disentangle our desire to help from our desire to please or avoid conflict or keep the peace?

Another of Carl Jung’s most significant contributions to psychology is the concept of the archetype. In the case of what we have been discussing, the archetype of the helper is useful. Individuals dominated by the archetype of the helper are driven by a need to nurture, protect, and care for others. Of course, the world would be a sorrier place without their soulful and compassionate generosity. But the desire to help, when it becomes compulsive or inappropriate to the situation, can result in a feeling of depletion, resentment, and confusion if one’s efforts are rebuffed. To discern if you are trapped in this kind of helping behavior, you need to examine your motives and your genuine intention for taking action.

Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg encourages students to examine their intentions as a way of understanding the motivation behind their actions. By honoring our intentions, we connect with the heart space that guides everything we undertake. Salzberg suggests that our intention is not a matter of will, “but about our overall everyday vision, what we long for, what we believe is possible for us.” To genuinely assess what motivates our intentions, she advises us to investigate the spirit of our endeavors and the emotions that drive it. “When my hand reaches to offer someone a book, only my heart knows whether I’m doing it because I like the person or because I think, Well, I’ll just give her this and perhaps she’ll give me what I want in return.”—Sharon Salzberg, “The Power of Intention,” O Magazine, January 1, 2004

Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg encourages students to examine their intentions as a way of understanding the motivation behind their actions. By honoring our intentions, we connect with the heart space that guides everything we undertake. Salzberg suggests that our intention is not a matter of will, “but about our overall everyday vision, what we long for, what we believe is possible for us.” To genuinely assess what motivates our intentions, she advises us to investigate the spirit of our endeavors and the emotions that drive it. “When my hand reaches to offer someone a book, only my heart knows whether I’m doing it because I like the person or because I think, Well, I’ll just give her this and perhaps she’ll give me what I want in return.”—Sharon Salzberg, “The Power of Intention,” O Magazine, January 1, 2004

This is helpful advice. When confronting a moral or ethical decision, we might ask ourselves: What is my true intention here? Am I stuck in a familiar pattern? Am I a hostage to someone else’s desire? What do I hope to achieve for myself? What am I avoiding? Is my action truly compassionate toward the other? Am I more afraid of confronting someone or courting displeasure than I am of being caught by bewitching energies?

(Learn more from meditation pioneer and world-renowned teacher Sharon Salzberg in my interview with her last year on Psychology Today, “Can Mindfulness Bring About Real Change?”)

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at