About three years ago, I started a series of poems in the voices of women caught in war. These poems arrived with absolute clarity, as if the speaker was sitting beside me, clutching my hand. First, there was Maria-Isabella, whose husband had gone to join the republican cause during the Spanish Civil War. Soon after, Marieke from the Netherlands and Myriam in Lebanon confided their urgent war stories. The poems that followed felt as if I were channeling. Later, they became part of my new book of poetry, M.

When I read these poems now, while images of wounded Ukrainian women and children haunt the media, the hair on the back of my neck goes up. My poems now seem prescient. Had I foreknowledge of what was to come?

How to explain this?

In one study, a third to a half of the 1,000 surveyed reported having “anomalous” dreams1. Many of us have premonitions, warning “flashes” that alerts us to an unseen danger or a fortuitous event. Perhaps we dream about a plane crash and cancel our flight. The next day, scrolling our newsfeed, we read about a plane crash. It’s not the plane we would have taken, but we’re chilled by the coincidence. One of the difficulties in substantiating precognitive events is how do we untangle precognitive knowing from mere coincidence?

In one study, a third to a half of the 1,000 surveyed reported having “anomalous” dreams1. Many of us have premonitions, warning “flashes” that alerts us to an unseen danger or a fortuitous event. Perhaps we dream about a plane crash and cancel our flight. The next day, scrolling our newsfeed, we read about a plane crash. It’s not the plane we would have taken, but we’re chilled by the coincidence. One of the difficulties in substantiating precognitive events is how do we untangle precognitive knowing from mere coincidence?

In 1966, in the village of Aberfan, Wales, an avalanche of coal waste from the Merthyr Vale Colliery poured down the mountainside, engulfing Pantglas Junior School and killing 144 people, 116 of them children in their classrooms. The scope of the horror spurred an inquiry into whether the disaster might have been prevented or foreseen. A consulting psychiatrist, J. C. Barker, decided to investigate.

According to reports, Dr. Barker “approached Peter Fairley, Science Correspondent for the London Evening Standard, who became an immediate ally in what developed into a nationwide investigation. One week later, Fairley published an appeal in the newspaper on 28 October 1966, requesting any persons who had experienced a premonition or dreamed of the tragedy before it occurred to get in touch. Widely syndicated in the national and psychic press, over the following two months Barker and Fairley received letters from 76 people all claiming to have experienced dreams or premonitions of the Aberfan disaster before it occurred. Some of the reported premonitions were so vague and indefinite that Barker judged there was nothing linking them with Aberfan, but 60 were deemed worthy of further investigation.”2 Here is a chilling recounting of a tragic dream by one of the children who died.

One of the saddest and most poignant dreams had been noted by the family of Eryl Mai Jones, aged 10, a pupil of Pantglas school who was killed in the disaster. Two weeks before, she had suddenly told her mother: “Mummy, I’m not afraid to die.” Her mother replied: “Why do you talk of dying, and you so young; do you want a lollipop?” “No,” Eryl said, “but I shall be with Peter and June” (two schoolmates). The day before the disaster she said to her mother: “Mummy, let me tell you about my dream last night.” Her mother answered gently: “Darling, I’ve no time now. Tell me again later.” The child replied: “No, Mummy, you must listen. I dreamt I went to school and there was no school there. Something black had come down all over it.” The next day, her daughter went off to school as happy as ever. That morning her mother was also due to go into Pantglas Junior school soon after her daughter, but curiously, just as Eryl Mai Jones left her home for the last time, the clock stopped at 9.00 am. As a result, her mother mistook the time, delaying her and saving her life. 3

Precognition derives from the Latin, praecognitio, “to know beforehand.” Precognition is the ability to obtain information about a future event, unknowable through inference alone, before the event actually occurs. A truly precognitive experience can only be confirmed after the fact. Research on paranormal phenomena is often flawed and difficult to obtain. For one thing, laboratory settings are not conducive to producing paranormal phenomena on-demand. Pinning down the mechanism of precognition is difficult partly because the idea that a future exists prior to our experiencing it pushes against our notion of free will and our experience of time. Time, as we experience it, flows forward, but some physicists disagree and assert that time flows both forward and backward.

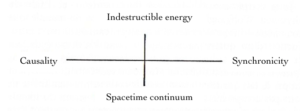

In their book, The Premonition Code, The Science of Precognition: How Sensing the Future Can Change Your Life, authors Theresa Cheung and Dr. Julia Mossbridge, a cognitive neuroscientist and director of the Innovation Lab at the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS), remark that current uncertainty exists about causality and time in philosophical and scientific circles. Some physicists believe the flow of time is “a complete illusion and we live in a series of ‘nows’ that are static and not flowing in any sense of the word.” As the authors suggest, this does not fit with our personal experience. While they fail to shed light on the specific how of precognition, Cheung and Dr. Mossbridge provide compelling examples and a tantalizing argument based on quantum theory and theories about the relativity of time.

Famous stories of precognition abound. Shortly before he was assassinated, Abraham Lincoln dreamed of a corpse laid out in funeral vestments in the East Room of the White House. In the dream, he asked a crowd of mourners who had died. The president, they told him. Several days later, the president was killed and his body laid in state in the East Room, exactly as he had dreamed.4

Famous stories of precognition abound. Shortly before he was assassinated, Abraham Lincoln dreamed of a corpse laid out in funeral vestments in the East Room of the White House. In the dream, he asked a crowd of mourners who had died. The president, they told him. Several days later, the president was killed and his body laid in state in the East Room, exactly as he had dreamed.4

Another example. In October 1913, C.G. Jung was on a train journey when he had an overpowering vision. As he later recounted in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, “I saw a monstrous flood covering all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps,” and recognized he was viewing “a frightful catastrophe.” The sea had turned to blood and uncounted thousands of bodies had drowned. Jung worried he was going mad. Two weeks later, the vision recurred. That August, the first World War erupted.

An older Jung recalled these visions and prophetic dreams and used them as evidence for his theories about consciousness. He called these Big Dreams, meaning they were archetypal and arose from the collective, not personal level of the unconscious. Our psyches, he posited, are composed of three interacting systems: the ego-complex, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious. The ego-complex functions in our everyday life and is the personality, the “I” with which we identify. The personal unconscious is composed of an individual’s ideas, thoughts, experiences, and fantasies hidden from the conscious mind, but which often directs behavior. The collective unconscious is that part of the psyche that does not arise from our personal experience but contains ancestral memories and the experiences of all sentient beings.

When we tap into the collective unconscious, we are in touch with information we could not have known from our own lives. This is the realm of inherited patterns handed down from our ancestors (archetypes) that shape how we view and relate to the world. It is the realm of Big Dreams, poetry, shamanism, mysticism, synchronicities, art.

Jung delved into esoteric traditions, Eastern theology, and occult practices, hoping to bridge the gap between metaphysics, depth psychology, and science. in a series of letters and exchanges with his patient and friend, the renowned Nobel Laureate in physics Wolfgang Pauli, Jung endeavored to uncover a unified theory that would bring psyche (mind) and matter into a more cohesive and congenial relationship. Both men were deeply interested in the nature of the universe in relationship to time, causality, meaning, and interconnectedness.5 But current psychological investigations have moved away from these grand metaphysical inquires, and have been superseded by research into AI, artificial intelligence, neuroanatomy, and neuroscience.

Jung delved into esoteric traditions, Eastern theology, and occult practices, hoping to bridge the gap between metaphysics, depth psychology, and science. in a series of letters and exchanges with his patient and friend, the renowned Nobel Laureate in physics Wolfgang Pauli, Jung endeavored to uncover a unified theory that would bring psyche (mind) and matter into a more cohesive and congenial relationship. Both men were deeply interested in the nature of the universe in relationship to time, causality, meaning, and interconnectedness.5 But current psychological investigations have moved away from these grand metaphysical inquires, and have been superseded by research into AI, artificial intelligence, neuroanatomy, and neuroscience.

Were my poems prescient? I have no way of knowing, but I stand with artists across millennia who have used their dreams and premonitions to produce works of art that touch a universal core. Might you turn your premonitions, hunches, dream images and visions into art? You’d be in grand company if you do. Consider the paintings of Goya, William Blake, the Symbolists, and Surrealists. Imagine keeping a premonition journal. Imagine dreaming of a very beautiful tree, one you don’t recognize, and a week later, on a new path, you see the tree from your dream. Perhaps the secrets of the mind are willing to reveal themselves to welcoming listeners.

References

1Pechey, R., and Halligan, P. (2011) Prevalence and correlates of anomalous experiences in a large non-clinical sample. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. Doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02024.x

2 “Foreseeing a Disaster?” Fortean Times February 2017

3 Ibid.

4 I describe this incident in more detail in a previous blog post “Can Dreams Be Prophetic?”

5 Paul Halpern details this fascinating relationship in his book Synchronicity: The Epic Quest to Understand the Quantum Nature of Cause and Effect (Basic Books, 2020).

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

If you found this blog interesting, you may also enjoy “Understand Your Dreams Using Jung’s ‘Active Imagination,’” “Soulwork: Why Dreams Are So Important in Jungian Analysis,” and “How Dreams Help Identify Areas We Need to Address,” as well as other blog posts on dreams.

Keep up with everything Dale is doing by following her on Facebook and .