Many years ago, my family spent a glorious summer in Maine while my husband attended classes at a local college. We rented a cabin on a pristine lake. Green manicured lawns led down to a sandy beach. Canoes and rowboats, picnic tables, and a swing set for the kids were all at our disposal. The days were sunny and warm, the nights star-filled and perfumed with pine. For two months, we lived in an enchanted world.

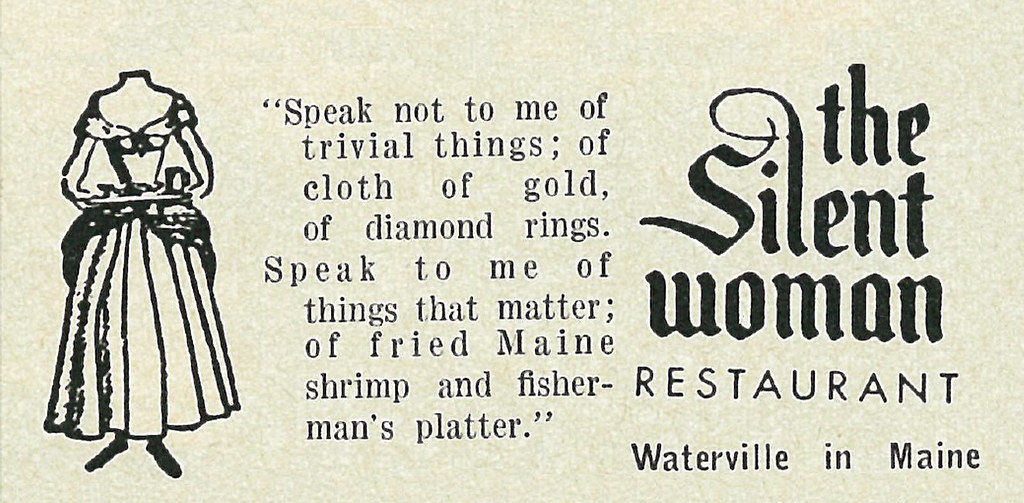

The enchanted world was also a traditional one. Our cabin had been in the owner’s family for decades, and the rules and decorum of past decades still held. Nearby, the small college town was traditionally charming and quaint. We did not go into town very often, except on the few occasions when we dined as a family at a well-established restaurant called The Silent Woman. See its sign above and below, an ad it ran in Ebony in 1970.

All these years later, this image has stuck with me: an image of violence and horror, of misogyny and gallows humor. What shocks my older self is that not once do I remember ever remarking on the depiction of the decapitated woman holding a serving tray, obviously silent because she has no head. I, too, was silent—in my anger, shock, and disgust, silent to myself and to others.

Back then, I was a silent woman—not because someone had chopped off my head—but because as a girl child I was tutored by my parents to be unoffending and pleasant; to be accepted. To be acceptable required that I act demure and accommodating at the expense of my own inclinations and feelings. The assumptions of that time, mid-to-late twentieth century, held that men were naturally superior, stronger, more rational than women, and that women were naturally inferior intellectually, and emotionally unstable compared to men. Men were thought to be the born leaders, the decision-makers with the power to name and dominate their world.

Cultural norms seem to have changed since then, but have they? What are the prevailing assumptions about gender? What was not so long ago unsayable for women—their experience of gender-related suffering and abuse—is no longer forbidden, but as we have sadly witnessed in public affairs, women speaking their truth are not necessarily believed.

Cultural norms seem to have changed since then, but have they? What are the prevailing assumptions about gender? What was not so long ago unsayable for women—their experience of gender-related suffering and abuse—is no longer forbidden, but as we have sadly witnessed in public affairs, women speaking their truth are not necessarily believed.

One of the consequences of speaking out but not being heard or believed relates to what Carol Gilligan and her co-author Lyn Mikel Brown began investigating in the 1980s and 1990s, tracing the coming-of-age journey of pre-adolescent girls into adulthood.

What the authors concluded then still holds true: girls entering adolescence learn to suppress their authentic voices so as not to appear “stupid” or “be too loud” or to signal whatever the current detested outsider label may be. Their book, Meeting at the Crossroads: Women’s Psychology and Girls’ Development (1992), based on a Harvard project, interprets interviews with 100 girls between the ages of seven and eighteen over a five-year period and traces their psychological development from childhood to adolescence. In this book and in her later work, Gilligan exposed how girls learn to self-censor in order to “be in a relationship.” If speaking out jeopardizes a girl’s place in the pack, even if her silence fills her with shame and a feeling of inauthenticity, she might sacrifice speaking her truth for the sake of approval and belonging.

As long ago as 1931, in “Professions for Women,” a famous speech to the National Society for Women’s Service, the British author Virginia Woolf described something she called “The Angel in the House,” a phantom that haunted her as a woman writer. This phantom would appear to her when she sat down to write and taunted her with self-doubt. How could she, a woman, ever presume to write a novel? The Angel, which in all effects was a demon, thwarted her real voice and her real thoughts. ”I will describe her as shortly as I can,” Woolf wrote. “She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish….” The Angel in the House demanded she be tender; flatter, deceive… and never let anyone guess you have a mind of your own.” Woolf concluded that out of necessity to write, she had to murder the Angel in the House.

For women born into more recent times, Woolf’s Angel may seem old-fashioned and irrelevant in the era of Beyoncé, Rihanna or Nadia Murad, just as for Woolf, in early twentieth-century England, the fact that in sixteenth-century England a woman accused of gossiping or speaking out of turn was called a “scold” and fitted with a bridle, an iron muzzle and bit placed over her head and clamped against her tongue, must have seemed like ancient history.

For women born into more recent times, Woolf’s Angel may seem old-fashioned and irrelevant in the era of Beyoncé, Rihanna or Nadia Murad, just as for Woolf, in early twentieth-century England, the fact that in sixteenth-century England a woman accused of gossiping or speaking out of turn was called a “scold” and fitted with a bridle, an iron muzzle and bit placed over her head and clamped against her tongue, must have seemed like ancient history.

We may now present ourselves as fist-in-the-air strong, feisty, sassy, and outspoken—but the struggle to tell our stories in our own voices without fear of reprisal continues. In many countries, a woman’s simple act of speech is a transgression. Our right to be witnessed, respected and heard is a relentless quest.

This quest is not only about image—do we look and sound strong?— but also about authenticity. Do we feel safe enough, secure enough, self-believing enough to show others our true self? Does our “outside “ reflect what’s inside? Can we enter public space with confidence in our ability to make ourselves heard? How much self-censoring do we do? Can we trust ourselves to listen to our still small voice and trust its truth?

While this piece addresses women directly, its message extends to any marginalized group that feels jeopardized by the dominant culture.

In her book When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice, the activist and writer Terry Tempest Williams begins by telling the reader that her mother, who died at the age of 54, had bequeathed Terry her journals but asked her to promise not to open them until after she died. When the author opened her mother’s journals, she found all the pages blank. Tempest writes: “What was my mother trying to say to me? Why did my other choose not to write in her journals? Was she afraid of her voice? Was she saying ‘Use your voice because I couldn’t or wouldn’t use mine’?”

In her book When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice, the activist and writer Terry Tempest Williams begins by telling the reader that her mother, who died at the age of 54, had bequeathed Terry her journals but asked her to promise not to open them until after she died. When the author opened her mother’s journals, she found all the pages blank. Tempest writes: “What was my mother trying to say to me? Why did my other choose not to write in her journals? Was she afraid of her voice? Was she saying ‘Use your voice because I couldn’t or wouldn’t use mine’?”

This profound legacy belongs to all of us who attempt to write on the blank pages of history. What do you find unsayable that needs to be spoken?

In closing, here are two opposing passages that state what’s at stake. Which do you claim and own?

turning into my own

turning on in

to my own self

at last

turning out of the

white cage, turning out of the

lady cage

turning at last

on a stem like a black fruit

in my own season

at last—Lucille Clifton, from An Ordinary Woman

What becometh a woman best, and first of all? Silence. What second? Silence. What third? Silence. What fourth. Silence. Yea, if a man should aske me till Domes daie I would crie silence, silence.

—Thomas Wilson, The Arte of Rhetorique, 1560

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at