It may not surprise readers of fiction that fiction writers have a very intimate relationship with our characters. We hear their voices waking and sleeping. Their stories live in us, they become family, that is, family we choose. Or perhaps I should say, family that chooses us. When I talk about my characters to a new audience, it’s almost as if I am introducing family members to strangers.

My characters reveal their stories to me, but not all at once and not in any linear way. And not surprisingly, the complications that arise in their lives echo subjects I’m drawn to. One subject that has concerned me for some time I call “Girls at Risk: The Enigma of Resilience.”

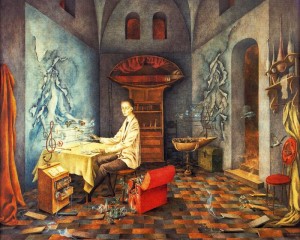

One of the threads in my debut novel, The Conditions of Love, is emotional resiliency, what qualities enable us to flourish despite bad beginnings. I didn’t realize I was writing about this subject until after I finished the book. I call these post-publication revelations “Writer’s Hindsight Learning.” It’s what the author doesn’t know she knows while she’s writing the book! What I mean is that when I’m engaged in the discovery aspect of writing, moving the story forward scene by scene and trying to be a good listener to my characters, I’m not in an analytic mode. For me, writing is a process of discovery. The themes pick me. This might sound counter-intuitive, even counter-productive, but it isn’t. It’s about trusting your unconscious mind to lead you where you need to go. That means I don’t outline or write out a plot before I begin. It means risking being in the unknown. It means suffering the woes of creative vulnerability. But I know no other way to get to the deeper layers of a story, to the story INSIDE the story.

One of the threads in my debut novel, The Conditions of Love, is emotional resiliency, what qualities enable us to flourish despite bad beginnings. I didn’t realize I was writing about this subject until after I finished the book. I call these post-publication revelations “Writer’s Hindsight Learning.” It’s what the author doesn’t know she knows while she’s writing the book! What I mean is that when I’m engaged in the discovery aspect of writing, moving the story forward scene by scene and trying to be a good listener to my characters, I’m not in an analytic mode. For me, writing is a process of discovery. The themes pick me. This might sound counter-intuitive, even counter-productive, but it isn’t. It’s about trusting your unconscious mind to lead you where you need to go. That means I don’t outline or write out a plot before I begin. It means risking being in the unknown. It means suffering the woes of creative vulnerability. But I know no other way to get to the deeper layers of a story, to the story INSIDE the story.

In fiction as in life, nothing destabilizes the identity of a young person as profoundly as turmoil in the home. I don’t mean this in any judgmental way. Quite the opposite. As a writer, I’m compelled to examine and speak the truth about the light and darkness inherent in human beings—the guilt, the sorrow, the joy, the indiscretions, the desire for freedom, the desire to survive no matter what.

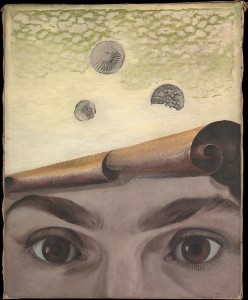

By destabilizing one’s identity I mean the confused and painful experience of not knowing who one is or where one belongs. It’s the feeling of rupture from the familiar and stable structures of one’s life. These can be existential crises that set us on a journey to find out who we are. We ask ourselves, “if this and this and this are no longer true in my life, who am I now?”

“You are not going to use me an an excuse again.” James Dean as Jim Stark arguing with his parents (Ann Doran and Jim Backus) in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

This dilemma—of finding one’s true self against the background of loss and impermanence—is at the core of The Conditions of Love, and now I see it shaping my second novel, a work in progress called Digging to China.

In both my novels, the young protagonists find themselves in home environments that are about to be disrupted. Their mothers are going through big changes. Their fathers are either absent, (Eunice in The Conditions of Love), or about to be left behind (Reenie in Digging to China). In his book, The Child, the psychologist Erich Neumann wrote: “Once we appreciate the positive significance of the child’s total dependency on the primal relationship, we cannot be surprised by the catastrophic effects that ensue when that relationship is disturbed or destroyed.”

Something Carl Jung once wrote has always haunted me and in some way has been an impetus for my work.

Something Carl Jung once wrote has always haunted me and in some way has been an impetus for my work.

“What usually has the strongest psychic effect on the child is the life which the parents (and ancestors too, for we are dealing here with the age-old psychological phenomenon of original sin) have not lived.” —Carl Jung, Introduction to The Inner World of Childhood by Frances G. Wickes (1927)

As a writer, I’m very interested in the entangled and entangling relationship between parents and children. In both my novels, the mothers are the major destabilizers in their daughter’s lives, while their fathers are absent and idealized. The unfulfilled desires of the mothers affect their daughters. These desires are either thwarted or encouraged by the decades they live in.

In The Conditions of Love, Eunice’s mother, Mern, has a craving to be a movie star. Hollywood and what it represented in the Fifties is quite different from the Hollywood of today. It’s hard for us to imagine how significant movies were in the Fifties. Movies stars were these gigantic, dazzling national icons. Everyone knew who Marilyn or Bogey was. So, we have a mother who yearns for a richer and more exciting life, and a child who yearns for a normal family.

But I have sympathy for Mern and hope readers will too. Her creativity is stifled. The novel is set in the Fifties before Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, before the birth control pill, and women’s lib. Mern IS over the top, but what can she aspire to? She’s trapped in her single mother, working class life. To be discovered as a starlet was one big dream for a lot of American women at that time. Of course this situation is horrible for her daughter. Indeed, a set up for calamity.

But I have sympathy for Mern and hope readers will too. Her creativity is stifled. The novel is set in the Fifties before Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, before the birth control pill, and women’s lib. Mern IS over the top, but what can she aspire to? She’s trapped in her single mother, working class life. To be discovered as a starlet was one big dream for a lot of American women at that time. Of course this situation is horrible for her daughter. Indeed, a set up for calamity.

In Digging to China, Reenie’s mother Nate is caught up in the political turbulence of the late Sixties. The novel begins one week after Robert Kennedy’s assassination, in June I968. In the course of the novel, Nate becomes radicalized and an activist for social justice. In Digging To China, specific political events precipitate internal transformation. Reenie becomes caught up in the dissolution of her parents’ marriage, and like Eunice, is launched on a journey of self-discovery.

Here is the opening of Digging to China. Reenie is listening to her parents fight in the room next door. You’ll hear how her imagination serves her in providing a sense of magic and wonder that leads to empowerment as she plots how to escape her distress.

Maplewood, New Jersey

May, 1968

Cages

They are at it again in the bedroom next to hers. Slippers thrown across the room, her mother’s scorched voice exploding in disgust. Her father commanding Control yourself, Nathalie. Reenie waits in the void of their aggrieved voices, ear to gap, the silence, and imagines her father smoking by the window, mother tense at the edge of the bed, cigarette butts burning to ash in the big glass ashtray. Her mother is Jewish and unhappy. (No one but Reenie notices this association, what she thinks of as her mother’s Jewish strangeness, the vague smile that twists into anger, the constant argument in her eyes.) Temperamental. Stubborn. Infuriating. Words her father labels her mother to be avoided at all costs, though Reenie is nothing like the brave and beautiful Nathalie. Nothing at all.

She should be used to this live rage scattershot in the night, but its randomness (her mother mutely seething at dinner, her father preoccupied but polite, cheerful even) undoes her, the violence chipping away at her confidence. Now she sits up in bed, hands clammy, heart sinking in a sea of blood and plugs her ears, Row row row your boat useless against the parental gale. Wakeful, she can’t not listen: her survival depends on it.

I want my fictional worlds to accurately convey the paradoxes, confusions, and moral dilemmas of human beings. Novels give us the experience of being alive in another person’s skin. How would we know about worlds we could never enter otherwise without our Toni Morrison, our Tim O’Brien, or Khaled Hosseini. Novels are direct avenues to compassion, something our world sorely needs to cultivate these days. And I have to say, writing my characters has taught me so much about risk, survival and resiliency. This is the great mystery of being a writer. We are transformed by what we write.