One definition of what separates us from other species is our ability to construct narratives from our random thoughts, memories, and imaginings. We are a species of storytellers. How and why we construct stories remains a mystery, one being explored by biologists, anthropologists, psychologists, neuroscientists, and researchers in semiotics and linguistics. One common thread in the research is that stories help us make sense of our lives.

Brian Boyd, author of On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction, suggests that we are hard-wired to tell stories. Boyd argues that art, in general, and fiction, in particular, have evolved from cognitive play and serve an evolutionary survival function. Our oldest stories, our myths and fairy tales — the story about the hunter and the stealthy lion, or the one about the fox and his invisible cape — may have determined whether our primordial ancestors lived or died. Over time, these stories have become embedded in the warp and woof of our culture, and while the danger of a humanly cunning lion may no longer fit our lifestyle, we get the point. Viewed literally, lions can maim us; taken symbolically, understanding and honoring the ways of an intelligent and powerful predator might help us navigate certain obstacles in our lives.

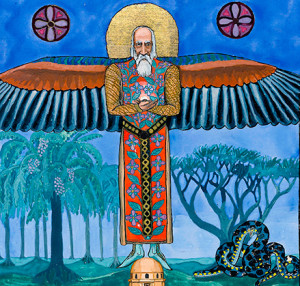

I’ve recently written several blogs about fairy tales. Fairy tales present simple stories that are still relevant as guides to the archetypal patterns in our unconscious minds. They are also teaching stories and cautionary tales that speak to the mythopoeic in our psyches, that aspect of our minds that think in metaphor and symbol. Like our ancestors who lived closer to nature, and like the cosmologies of many indigenous peoples, we, too, have the capacity to experience a tree as a spirit helper or a demon or a bewitched prince. While the earliest folk tales emerged from peoples who possessed a less sophisticated notion of the world, their repertoire of emotions and the stories they wove around them were not dissimilar to our own. Greed, loneliness, jealousy, sorrow — these continue to be our human burden. Cinderella, Bluebeard, Sleeping Beauty are our contemporaries, their journeys to selfhood or self-destruction familiar to our modern souls.

I’ve recently written several blogs about fairy tales. Fairy tales present simple stories that are still relevant as guides to the archetypal patterns in our unconscious minds. They are also teaching stories and cautionary tales that speak to the mythopoeic in our psyches, that aspect of our minds that think in metaphor and symbol. Like our ancestors who lived closer to nature, and like the cosmologies of many indigenous peoples, we, too, have the capacity to experience a tree as a spirit helper or a demon or a bewitched prince. While the earliest folk tales emerged from peoples who possessed a less sophisticated notion of the world, their repertoire of emotions and the stories they wove around them were not dissimilar to our own. Greed, loneliness, jealousy, sorrow — these continue to be our human burden. Cinderella, Bluebeard, Sleeping Beauty are our contemporaries, their journeys to selfhood or self-destruction familiar to our modern souls.

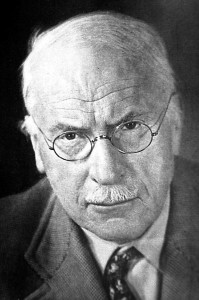

One way to more fully experience the wisdom of fairy tales is to write your own. Through objectifying the contents of our unconscious by drawing, sculpting, writing, dancing, we find the healing symbols within. The Red Book is a record of Carl Jung’s own plunge into an almost psychotic state after his break with Sigmund Freud in 1913. Characters from his unconscious welled up in his conscious mind. Methodically, with terror and fortitude, he recorded his dialogues with these characters as if they were flesh and blood and Jung even painted images that illustrated his experiences with them. Jung sometimes feared during this period that he was toppling into a psychotic state, but by working consciously with these figures, he found he was able to hear their wisdom “from the other side.” These encounters later lead to his theory of Active Imagination, which he somewhat describes in this advice to an analysand about working with her dreams.

One way to more fully experience the wisdom of fairy tales is to write your own. Through objectifying the contents of our unconscious by drawing, sculpting, writing, dancing, we find the healing symbols within. The Red Book is a record of Carl Jung’s own plunge into an almost psychotic state after his break with Sigmund Freud in 1913. Characters from his unconscious welled up in his conscious mind. Methodically, with terror and fortitude, he recorded his dialogues with these characters as if they were flesh and blood and Jung even painted images that illustrated his experiences with them. Jung sometimes feared during this period that he was toppling into a psychotic state, but by working consciously with these figures, he found he was able to hear their wisdom “from the other side.” These encounters later lead to his theory of Active Imagination, which he somewhat describes in this advice to an analysand about working with her dreams.

“I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can — in some beautifully bound book,” Jung instructed. “It will seem as if you were making the visions banal — but then you need to do that — then you are freed from the power of them. . . . Think of it in your imagination and try to paint it. Then when these things are in some precious book you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be your church — your cathedral — the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal. If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them — then you will lose your soul — for in that book is your soul.”

To begin, what is your favorite fairy tale? Most of us have a tale that has lingered since childhood, one that strikes a strong resonance in us. Rediscover the story that seems to be “yours” and reread it. That you choose one fairy tale over another is significant. Part of your inquiry is to ask yourself why. Does this tale say something about your life? Is your own myth about rejection or abandonment? Do you feel victimized and left in the ashes like Cinderella? Or pressured to be the hero and save your family from poverty like Jack in “Jack in the Beanstalk?” After you read your chosen fairy tale, ask yourself these questions:

To begin, what is your favorite fairy tale? Most of us have a tale that has lingered since childhood, one that strikes a strong resonance in us. Rediscover the story that seems to be “yours” and reread it. That you choose one fairy tale over another is significant. Part of your inquiry is to ask yourself why. Does this tale say something about your life? Is your own myth about rejection or abandonment? Do you feel victimized and left in the ashes like Cinderella? Or pressured to be the hero and save your family from poverty like Jack in “Jack in the Beanstalk?” After you read your chosen fairy tale, ask yourself these questions:

- What is my reaction?

- What does this stir up in me?

- Have I lived something similar?

- What are the symbols in the story and what are my associations to them?

You might want to write your answers in a journal you set apart for this work. The magic of fairy tales is that they transport us into an enchanted realm that is itself “set apart” from ordinary life. By recording your responses to your fairy tale, you honor the creative storyteller in you. In attempting to become conscious of the story, you make sense of yourself.

The second part of this exercise is to rewrite your favorite tale using the story you chose as a jumping off point. The goal here is to get “inside” the story and write it from inside out. “The good writer,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “seems to be writing about himself, but has his eye always on that thread of the universe which runs through himself and all things.” This exercise isn’t about crafting a story that will make you a famous writer, it’s about discovering the richness, subtlety, and astonishing wisdoms of your inner life.

The second part of this exercise is to rewrite your favorite tale using the story you chose as a jumping off point. The goal here is to get “inside” the story and write it from inside out. “The good writer,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson, “seems to be writing about himself, but has his eye always on that thread of the universe which runs through himself and all things.” This exercise isn’t about crafting a story that will make you a famous writer, it’s about discovering the richness, subtlety, and astonishing wisdoms of your inner life.

The guidelines for writing your new fairy tale are simple:

- Create a new setting for the story you chose. The writer Eudora Welty, who grew up in and wrote about the Deep South, reminds us that “feelings are bound up with place.” Instead of beginning with “Once upon a time” or “Long ago,” set your story somewhere specific. NYC, 2017. St. Petersburg under Tsar Nicholas. Setting is locale, period, weather, time of day. It includes sense perceptions —smells, tastes, sounds. What about a fairy tale set in a Wisconsin barn or a bar in New Orleans?

- Choose a character from your favorite tale and tell the story from his or her point of view. Empathy is the ability to put oneself in another person’s shoes. What would we learn if we heard the story of Rumpelstiltskin from Rumpelstiltskin’s point of view? Set your wild imagination free. What if Cinderella’s stepsister confesses she didn’t want to marry the prince, she only wanted to wear his splendid uniform!

In creating this new story you will surprise yourself. The process is one of discovery. Pay attention to what you dream during this process. With inner and outer vision, discover what animals appear to you. What song plays on the breeze? Don’t overthink, strive or fret. There are no rules. Whatever reveals itself wants your attention.

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at