In 1932, a new radio show called The Shadow, adapted from a popular pulp fiction magazine, premiered on the nation’s airwaves. Its narrator, Frank Readick, had the perfect menacing voice to embody the show’s protagonist. Lamont Cranston, a rich man-about-town by day, morphed into the indefatigable and invisible crime-buster, The Shadow, when summoned to uproot evil. The show’s signature line was: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!” A sinister, knowing laugh followed. Audiences were mesmerized. In later episodes, the young Orson Welles voiced The Shadow.

In the thirties, the economic and emotional effects of the Great Depression still lingered in the public’s mind. Awareness of the spread of fascism in Europe and its threat to democracy captured headlines. The country was ripe for entertainment that provided a character endowed with superhuman powers and knowledge of enemy-defeating esoteric practices. In our own troubled times, media icons, cult stars, and a handful of political figures attract similar projections. Wishful thinking, a collective sense of doom, nostalgia for a previous (and non-existent) innocent era, and a rejection of the hardships of change have elevated certain leaders to savior status.

In the thirties, the economic and emotional effects of the Great Depression still lingered in the public’s mind. Awareness of the spread of fascism in Europe and its threat to democracy captured headlines. The country was ripe for entertainment that provided a character endowed with superhuman powers and knowledge of enemy-defeating esoteric practices. In our own troubled times, media icons, cult stars, and a handful of political figures attract similar projections. Wishful thinking, a collective sense of doom, nostalgia for a previous (and non-existent) innocent era, and a rejection of the hardships of change have elevated certain leaders to savior status.

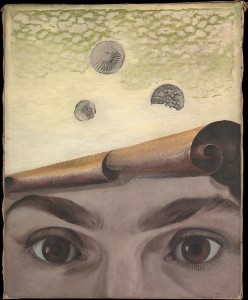

in Jungian terms, the “shadow” refers to those aspects of ourselves we reject. They remain hidden from our conscious mind but often appear in dreams as fearful or hated figures. Whenever we have a strong hostile reaction to a person or to an idea, or feel overly self-righteous, we can be sure the shadow is at hand, showing us something about ourselves we do not wish to see. That’s because the shadow presents a threat to our ego ideal, the good personality with which we identify.

We play out the tension between our ego ideal (I am a smart, respectable, dutiful, kind father, daughter, wife, son) and the reality of our more complex wholeness, which includes split-off aspects of the Self, in our personal relationships but also on the broader stage among religious or ethnic groups and among nations.

J. Edgar Hoover, the first Director of the FBI who served under eight presidents, offers an example of someone in conflict with his shadow. A notorious homophobe, he was instrumental in persuading Present Dwight Eisenhower to ban gays from all government jobs. For decades, Hoover engaged in illegal wire-tapping and spying activities against his enemies and kept extensive dossiers on their sexual and private lives. His rationale was that he was upholding the values and laws of this country. After his death, several of his biographers found evidence that Hoover was himself a man of secrets and lived a closeted gay life.

J. Edgar Hoover, the first Director of the FBI who served under eight presidents, offers an example of someone in conflict with his shadow. A notorious homophobe, he was instrumental in persuading Present Dwight Eisenhower to ban gays from all government jobs. For decades, Hoover engaged in illegal wire-tapping and spying activities against his enemies and kept extensive dossiers on their sexual and private lives. His rationale was that he was upholding the values and laws of this country. After his death, several of his biographers found evidence that Hoover was himself a man of secrets and lived a closeted gay life.

No one likes to feel vulnerable, humiliated, or ashamed. No one wants to show their neediness, but all humans share the same instincts and emotions. If we can bring compassion to the disowned parts in our own psyche, we have a better chance of extending compassion to others who are needy, hurt, vulnerable.

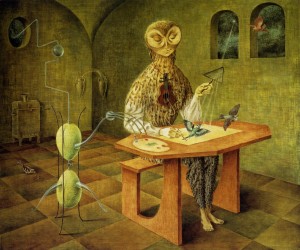

The aspects we deny in ourselves are not always negative. Some psychotherapists refer to a “golden shadow,” disowned unconscious energies that fuel and are necessary for a vital life. A young man may cut off his creativity as a dancer to conform to some societal or family norm. A young woman may fear being too brainy or too assertive to fit stereotypes reinforced by her upbringing. Our personal shadows are shaped by individual experiences but also by the society and family in which we live.

When shadow material is guiding our thoughts and actions, we’re inclined to see the other who carries our projections as all bad. What we cut off in ourselves we see outside of us and respond by attacking those traits in others with displaced aggression. In some instances, this leads to scapegoating, a process in which we attribute all the “badness” to another person or persons who are persecuted and exiled from the dominant group. When we own our split-off parts, we no longer need to project them onto others.

I’ve written before about Jung’s concept of the shadow (“How Facing Our Shadow Can Release Us from Scapegoating”), and it’s a topic worthy of further exploration. Jung’s contention was that through the inner work of recognizing and owning our shadow and integrating it as part of one’s totality we can hope to balance our personal nature and prevent the repressed aspects from spilling out into the world. This is one of the ethical dilemmas of our time, a global era that is ripe with fear, hatred, and blame.

I’ve written before about Jung’s concept of the shadow (“How Facing Our Shadow Can Release Us from Scapegoating”), and it’s a topic worthy of further exploration. Jung’s contention was that through the inner work of recognizing and owning our shadow and integrating it as part of one’s totality we can hope to balance our personal nature and prevent the repressed aspects from spilling out into the world. This is one of the ethical dilemmas of our time, a global era that is ripe with fear, hatred, and blame.

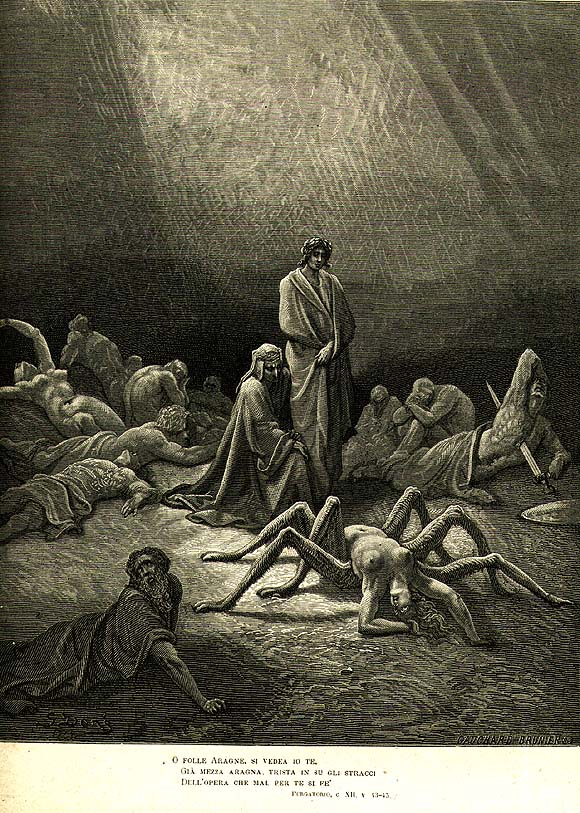

What we don’t realize is that the battle between opposites is within us. Locked away in our unconscious mind are unacceptable drives, fantasies, and beliefs that appear in dreams as dangerous invading forces—thugs and vigilantes, the figure of an arrogant neighbor, a Nazi soldier, or the ex-partner we demonize and disdain. In biblical stories, fairy tales, and literature we can easily identify the polarized parts: Cain and Abel, God and the Devil, wicked stepmothers and innocent stepdaughters, derelict fathers and victimized children. Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello and Lady Macbeth are two of the most fascinating evil characters in literature. With our more aware social conscience, we might question why the great bard made Othello a person of color and a scheming woman the engine of tragedy in Macbeth. Jung suggests that our task is to peer within, to acknowledge the shifty, malevolent, or frightened parts and make them our allies.

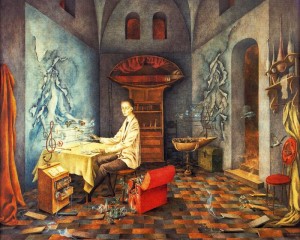

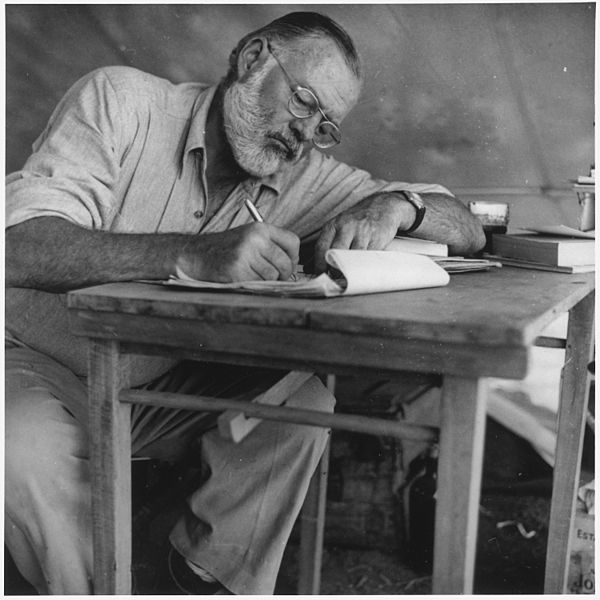

As a novelist, I pay a lot of attention to the shadow aspects of my characters, what they don’t know about themselves but which the reader will learn by reading the book. I am each character’s psychoanalyst, digging deeper into their psyches to reveal the driving forces and the points of conflict in their being. In early drafts, I think I know what’s going on in their internal lives, but just as in analysis, it takes time and great patience for a character to reveal herself to me. Sometimes I’m saddened by what I learn. Sometimes I have a great “Aha” feeling when the contradictions in their actions and words cohere and make sense.

When we say writing novels is not for the faint of heart, we mean that as writers, we are deeply invested in the world we’ve created. We expend vast amounts of time and energy in the act of creation. We want our characters to evolve and grow wise. But since art follows life, and life can’t be counted on for producing happy endings, so neither can we guarantee fulfillment for our characters. In The Conditions of Love, for instance, part of me wanted troubled, self-centered Mern to reappear reformed later in her daughter’s life, but Mern wouldn’t have it. Instead, resilient Eunice had to grow independent and find love on her own.

How can you recognize your shadow? Notice when you have a spontaneous and disproportionate response to a person, an idea, or a group. Take some time to entangle what has agitated you. What characteristics do you find most problematic in the other? Where might they live in you?

This post appeared in a slightly different form on Dale’s blog on Psychology Today. You can find all of Dale’s blog posts for Psychology Today at

A new realm of Envy Hell opened up to me after I became a published writer. Google “Writer’s Envy” and a whole host of links appear. This is no surprise since we artists have our eye on immortality, and fame is a very small ship onto which many hope to sail. I do find it ironic that while envy is the engine that drives many works of literature—think Agamemnon taking Briseis from Achilles and Achilles sulking in his tent for three years; Iago envying Othello or Edmund Edgar in King Lear; or Amy March’s envy of Jo in Little Women. Authors are forever weaving plots around envy; we are mighty resistant to ‘fessing up about our own.

A new realm of Envy Hell opened up to me after I became a published writer. Google “Writer’s Envy” and a whole host of links appear. This is no surprise since we artists have our eye on immortality, and fame is a very small ship onto which many hope to sail. I do find it ironic that while envy is the engine that drives many works of literature—think Agamemnon taking Briseis from Achilles and Achilles sulking in his tent for three years; Iago envying Othello or Edmund Edgar in King Lear; or Amy March’s envy of Jo in Little Women. Authors are forever weaving plots around envy; we are mighty resistant to ‘fessing up about our own.

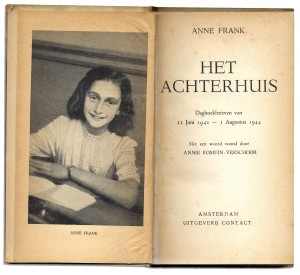

I’ve been haunted by an image of a forest. There’s a bare tree, lots of dead leaves. A man’s shoe. A child’s shoe. The feeling-tone is ominous. I suspect what the images relate to, but I don’t know the story. Yet.

I’ve been haunted by an image of a forest. There’s a bare tree, lots of dead leaves. A man’s shoe. A child’s shoe. The feeling-tone is ominous. I suspect what the images relate to, but I don’t know the story. Yet.

Or, a new character shows up in a dream and tells you her heartbreaking story. Insights drop into your consciousness from odd places—bits of conversation overheard at the market, NPR stories—I’ve had to pull off the road when listening to Iraqi war veterans speak of their experiences, my mind/heart brimming with their graphic tales.

Or, a new character shows up in a dream and tells you her heartbreaking story. Insights drop into your consciousness from odd places—bits of conversation overheard at the market, NPR stories—I’ve had to pull off the road when listening to Iraqi war veterans speak of their experiences, my mind/heart brimming with their graphic tales.