Dream Incubation: Solving Problems in Your Sleep

What if we could direct our dreams? What if we could ask our dreams for solutions to our most pressing problems and receive important answers while we sleep? What if we could deliberately seed our unconscious mind to evoke helpful dreams?

This is the territory of dream incubation, a practice dating back to Babylonian civilization and extending into our current time. The ancients developed their own language and explanations for human behavior, and they well understood the relationship between trauma, memory, creativity, healing, and dreams. As their descendants, we are the recipients of their knowledge, and today discoveries in neuroscience and psychology expand the old understandings. Depth psychology shares with shamanic and other dream interpretation traditions the practice of extracting meaning from symbolic dream images. (Why do I continue to dream about a burning house? What does the image mean?) Innovations in imaging technology and brain studies bring to dreamwork new insights about the anatomy of dreaming and techniques to manipulate dreams for purposeful answers or to alleviate nightmares.

One reality about dreaming, however, has remained constant since human existence: the unconscious mind is inaccessible to the conscious mind. Dream incubation, then and now, is an attempt to connect the dreaming “me” to the wakeful “me,” and to access the valuable insights hidden within.

I recently had a surprising experience with dream incubation. After reading Machiel Klerk’s easy-to-follow book, Dream Guidance: Connecting to the Soul Through Dream Incubation, I asked for a dream to help me understand my feelings of abandonment that had no discernible cause. That night I had a joyful dream of getting a puppy as I young child. In the morning, a long-buried memory of a painful childhood incident flashed into my mind.

When I was nine, after much pleading, my parents bought me a puppy. It was love at first sight. One day about a month later, I arrived home from school to discover the puppy was gone. Heartbroken, I asked my parents what happened. They told me the dog had run away. I went to my room and sobbed, convinced the dog would not have run away if she loved me. Feelings of failure and abandonment took root. Years later, my father confessed they did not want to take care of the dog and gave her away. The emotional repercussions of his lie never occurred to him.

My challenge is to untangle the symbolism in the dream, its meaning and relevancy to my life now, but I doubt I would have had the dream and the morning recollection had I not incubated a question to the dream maker. I use the term “dream maker” as a personification of that which is in our unconscious minds that composes and directs our dreams.

The root of the word incubate is the Latin incubare, (in-‘upon’ + cubare ‘to lie’), referring to how a mother bird sits on her eggs with patient nurturing attention, an apt image for nurturing our dreams. Harvard professor Deirdre Barrett straddles the worlds of academic psychology and neuroscience. Over the last decades, she has been a chief investigator in dream research. Her newest book, Pandemic Dreams, explores how collective traumatic events such as the COVID pandemic, 9/11, or the experiences of POWs in Nazi prison camps share similar patterns or motifs in dreamers’ nightmares. In a previous book, The Committee of Sleep, she delves into how the dreams of creatives in art, science, and technology have informed their work.

Here’s a brief recap of her instructions for incubation:

Write down the problem or question and place this by the bed. Be clear, specific and brief.

Review the problem or question for a few minutes just before going to bed.

Once in bed, visualize the problem as a concrete image. For instance, if you are experiencing a sense of isolation, imagine yourself alone in a house, looking out a window wearing a sad face.

Tell yourself you want to dream about the problem just as you are drifting off to sleep.

Keep a pen and paper—perhaps also a flashlight with a red lens or pen with a lit tip—on the night table. I use a small Dictaphone.

Upon awakening, lie quietly before getting out of bed. Note whether there is any trace of a recalled dream and invite more of the dream to return if possible. Write it down.

Depth psychologists Machiel Klerk, Stephen Aizenstat, Robert Bosnak, and others recommend creating a ritual around dream work. Ritual played a crucial part in dream incubation in antiquity. The ancient aspirants were advised to sleep in a sacred precinct—a temple, or the Asclepions in Greece, or in tombs, as was the custom of the North African Berbers, or on mountaintops favored by indigenous peoples. The idea was to retreat to refuge or sanctuary far from the daily world. Today sleep experts concur, and recommend creating a calm, darkened, digital-free space used only for sleep.

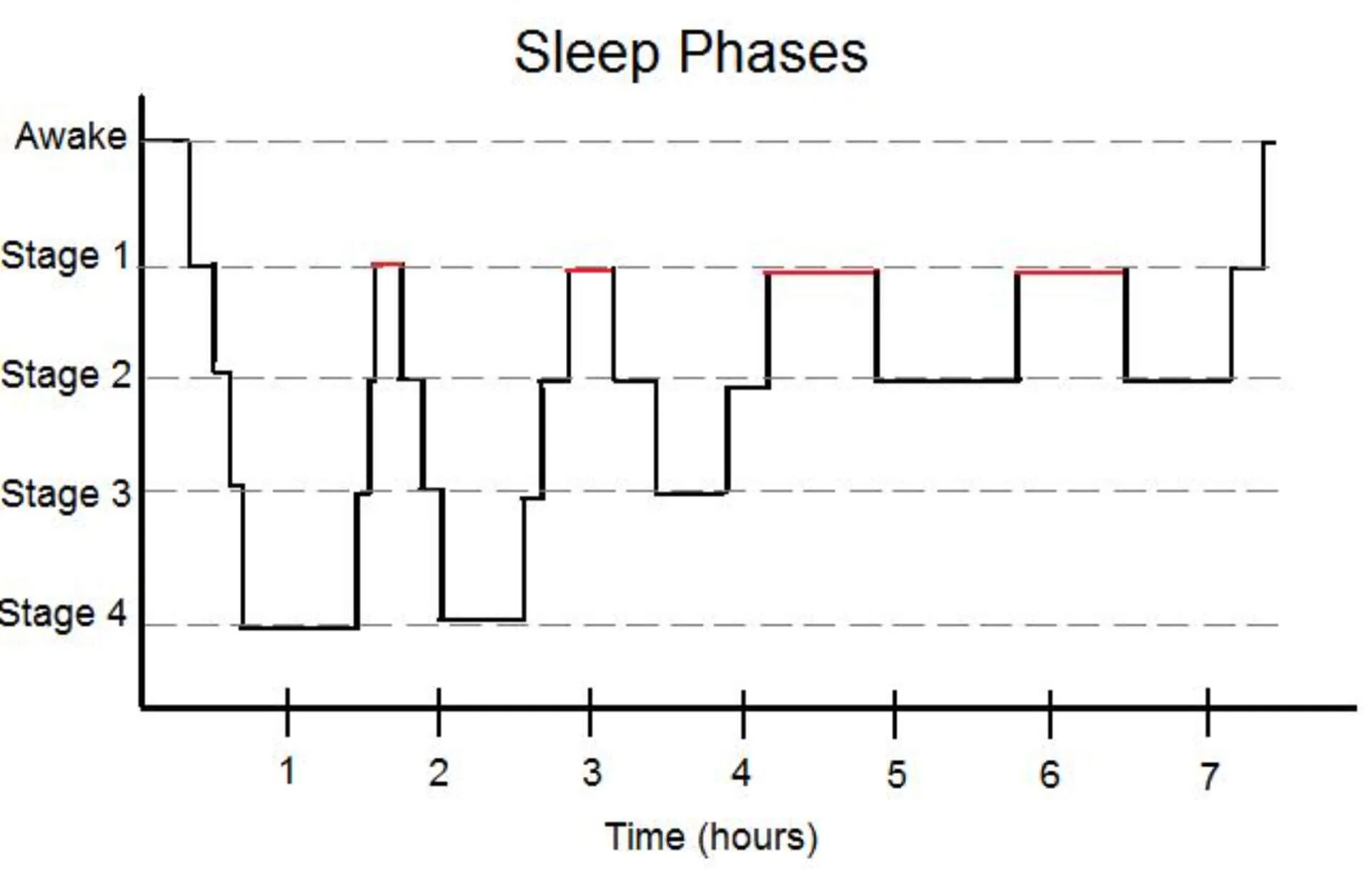

If rituals around dreaming harken back to earlier times, the latest research in sleep provides new discoveries about what happens during the four stages of sleep. Scientists have determined that the non-REM 1 stage called hypnagogia, an interval between wakefulness and sleep when our brain is transforming electrically and chemically as it enters unconsciousness, is a time when we are most suggestible to outside prompts.1 The prompts may be in the form of spoken words, which become visual images in our minds. These images enter our dreams. Positive suggestions played on audio tapes become lived experiences through dreams. New therapies that track dream stages and provide auditory biofeedback (Targeted Memory Reactivation) are being employed to interrupt nightmares and guide the dreamer to rewrite disturbing dreams.2

The combined efforts of researchers and depth psychologists have reawakened a primal wish in us to befriend the wise dream-maker within. Together, neuroscience and depth psychology are two portals into the mystery of dreams.

[1] Adam Haar Horowitz, “Dormio: A Targeted Dream Incubation Device,” Consciousness & Cognition, August 2020.

[2] Francesca Borghese et al., “Targeted Memory Reactivation During REM Sleep in Patients With Social Anxiety Disorder,” Frontiers of Psychiatry, June 2022.