Honoring Your Inner Witch

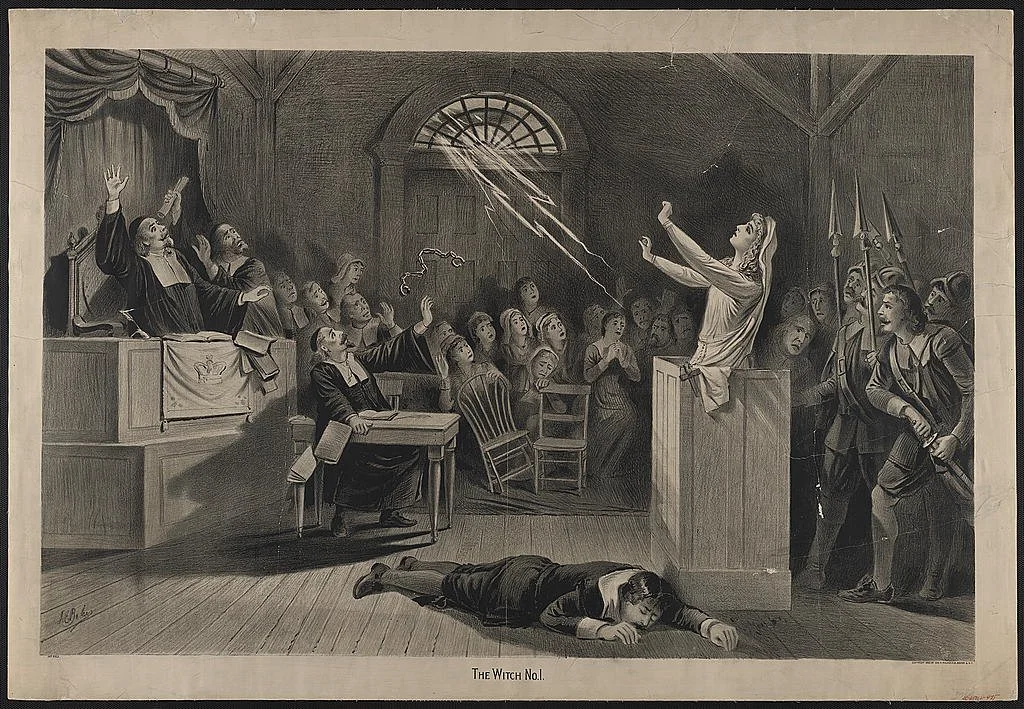

Image: The witch no. 1 (1892) lithograph by Joseph E. Baker (1837-1914) imagines events during the Salem Witch Trials. Geo. H. Walker & Co./ Public Domain

Has anyone ever called you a witch? Have you called someone else a witch? How would you describe a “witchy” person? Can a man be witchy?

Once, when I was little, my mother told me she had eyes on the back of her head. She convinced me that she could see through walls to whatever mischief I was up to, so I’d better not get into the cookie jar. I thought she was a witch and had special powers against which I was powerless.

Sometime later, I played the Wicked Witch of the West in a camp production of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. I still remember the ecstatic power I felt in saying my lines.

I have torn the scarecrow into pieces, battered the tin woodsman and tamed the lion. And now for you, Dorothy. Heeheehee.

In October, we costume up for Halloween, once a sacred day, Samhain, celebrated by the ancient Celts to mark the end of summer and the harvest season. The boundary between the living and the dead was thought to grow thin at this time. Celebrants then dressed in costumes as a disguise to confuse the spirits of the dead, who were said to return to the living. Later, the Catholic Church absorbed some of the ideas of the pagan ritual, transforming it into All Saints’ Day to honor their saints. The night before All Saints’ Day was called All Hallows’ Eve, which later became our Halloween.

Wise women, herbalists, midwives, and healers who were trusted and revered for their benevolent powers in Irish and Celtic culture became, under Christianity, feared, mistrusted, persecuted, and killed, believed to be cunning allies of the devil.[1] Great witch hunts were conducted throughout Europe from the 15th through the 18th centuries, and to a lesser degree in the American colonies. Innocent women could be accused by neighbors or religious authorities of causing crop failures, natural disasters, for casting spells, and working black magic. Punishment was severe: the women were tortured and drowned or burned at the stake.[2]

This forthcoming Halloween, giggling young people will appear at our doors dressed as witches in black pointy hats and warty masks with little understanding of how witches became the terrifying presences we still assign to them. This is because witches strike us as uncanny. In the story of “Snow White,” the evil queen witch is a shapeshifter, appearing in different disguises at the dwarves’ house to poison Snow White. The Baba Yaga, a witch of Slavic origins, is represented as an old haggard woman who flies through the air in her hut built on chicken legs. While we may be frightened of serial killers, random shooters, muggers, and psychopaths, the belief that witches have supernatural powers, invisible and unnameable skills, and even the ability to communicate with the dead, terrifies us. Nor is this fear something modern people have put aside. As recently as 2023, women in several African countries have been accused of witchcraft and suffered brutal consequences.[3]

At the heart of the fear of witches is a fear of female power. In the ancient traditions—Norse, Celtic, Anatolian, Greek, Roman—nature goddesses ruled over the domains of life and death, embodying the earth’s fertility, the motion of the seas, the sun, moon, and stars. As Judeo-Christian religions spread, God the Father replaced Mother Earth as the creator of the cosmos and its ruling force. Goddess worship was forbidden, the ancient female deities vilified and deemed consorts of Satan.[4]

The current controversy over women’s rights and the role of women in our culture brings the issue of “witchy women,” a negative projection of dark powers onto women, upfront and personal. Projection is a psychological term used to describe the displacement of one’s own negative or uncomfortable traits, thoughts, and behaviors onto another person or group. In dominant patriarchal cultures, women hold a subordinate position in domestic, social, and work relations. As a subordinate or marginalized group, they pose less of a threat to the power structures. I wrote more about this in a previous post, “Mothers, Witches, and the Power of Archetypes.”

The projection of evil onto the feminine, the “other gender,” and targeting specific women as witchy, ignores the fact that both men and women embody masculine and feminine traits—that is, human traits—our ability to care, nurture, soothe, protect our young, as well as the capacity to do harm. In myths and fairy tales, witches can be creators or destroyers and are sometimes both. To paraphrase the poet Walt Whitman: “We are large. We contain multitudes.” In embracing our contradictory nature, the good and difficult parts, we are embracing our wholeness as complex beings.

An interesting exploration this Halloween might be to ask ourselves: Who is the witch within me? What kind of witch is she? Does she have a name? What does she want from me? From others? What are her fears? What are her powers, and how does she use them? If she could call herself something else, what would she say?

[1] Green, Karen, and John Bigelow, “Does Science Persecute Women? The Case of the 16th-17th Century Witch Hunts,” Philosophy, Vol. 73, No. 284 (Apr. 1998) pp. 195-217

[2] Ehrenreich, Barbara, and Deirdre English. Witches, Midwives, & Nurses: A History of Women Healers. Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2010.

[3] Igwe, Leo, “Witch-Hunting: A Culture War Fought with Skepticism and Compassion,” Skeptic, March 18, 2025

[4] Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wife? Archeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans. 2005

If you found this post interesting, you may also want to read: