Understand Your Dreams by Engaging Them Using Jung’s “Active Imagination”

Image: Le Rêve (The Dream) by Henri Rousseau (1910) Source: Museum of Modern Art/Public Domain

Dreams are a marvel, worlds of wonder filled with phantasmagoric images, surreal plot twists that have their own logic even as they turn us inside out with their shifting points of view. Dreams take us high and drop us low. Whether we’re flying over the Manhattan skyline or being chased through a cornfield by a bull, we sense that our dreams are trying to communicate something—perhaps something essential—to our waking selves. We suspect that what is hidden from one part of our minds in the day-world—our unspoken worries, our secret loves, the destiny we fear to follow—becomes manifest in living color in our dreams.

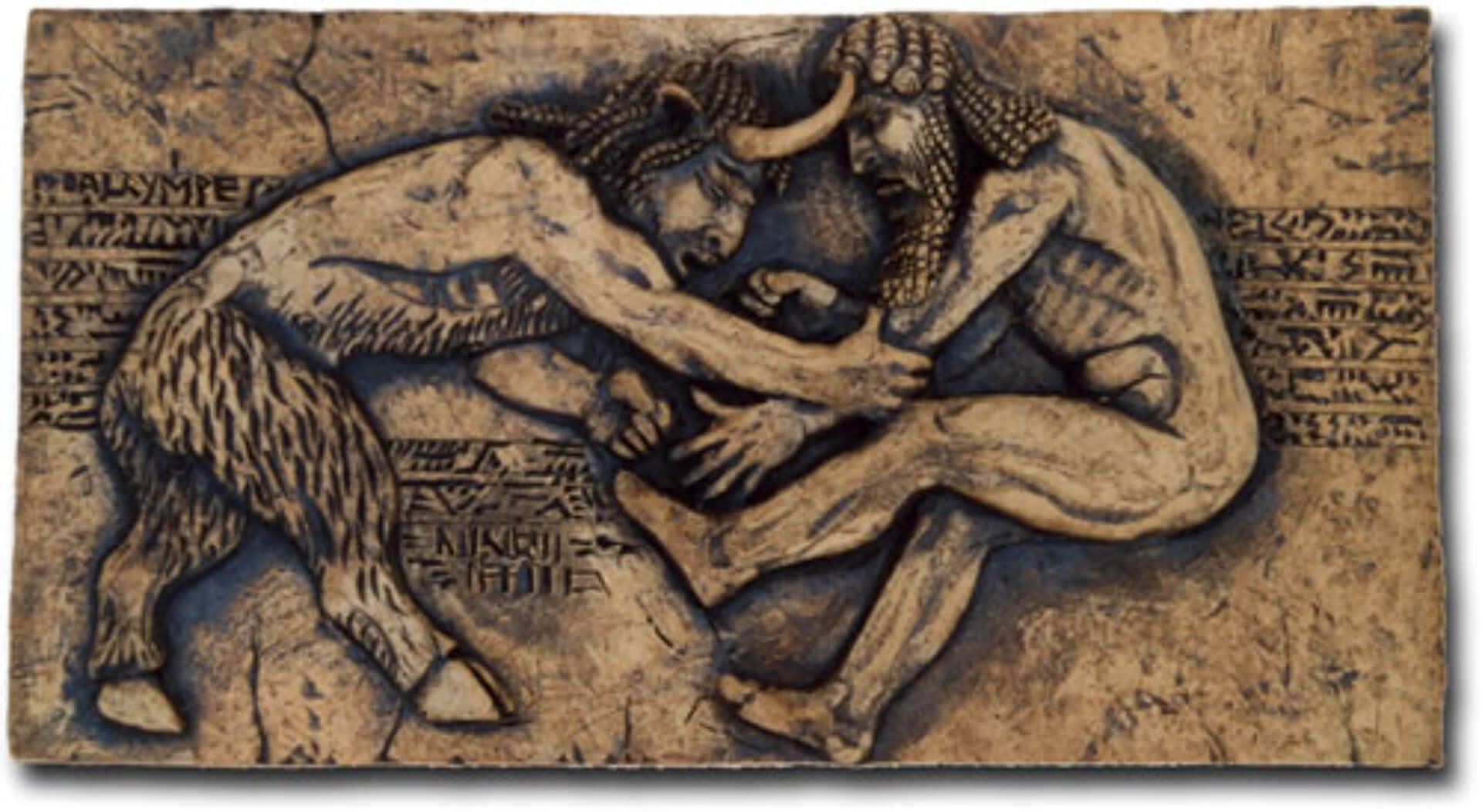

As far as we know, humans have always dreamed. Some of our earliest written stories include dreams. In the first tablet of our oldest epic poem, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, just before he encounters his doppelganger Inkidu, Gilgamesh dreams of a rock and an axe falling from the sky; his mother explains to him that these images foretell the arrival of “a mighty comrade.” In Homer’s Odyssey, Penelope dreams of fifty geese being killed by an eagle, a wish fulfilled when her husband Odysseus returns and slays the suitors plaguing her. And in the Old Testament, Joseph achieves fame by interpreting Pharaoh’s dream about fourteen cows, seven fat, seven lean.

On every continent groups still exist that consult dreams to foretell the future or connect with the Divine. Even some of us “non-believers” decorate our bedrooms with dream catchers. Why? As much as we might want to reject the notion of an invisible world that influences our day-life, don’t we all suspect there is a meaning and purpose to our dreams?

Marie-Louise von Franz, a scholarly colleague of Jung’s, wrote that dreams “are the voice of nature within us.” Dreams may be the sacred place where human and cosmos meet and interact. In The Collective Works, Jung elaborates:

“… in dreams we put on the likeness of that more universal, truer, more eternal man dwelling in the darkness of primordial night. There he is still the whole, and the whole is in him, indistinguishable from nature and bare from all egohood. It is from these all-uniting depths that the dream arises . . .” (CW 10).

On the scientific side, we are learning more about the neuroscience of dreams than ever before. As Sander van der Linden describes in an article in Scientific American, one hypothesis, based on where dreaming occurs in the brain, speculates that dream stories “may be stripping the emotion out of a certain experience by creating a memory of it.” Other scientists speculate that the purpose of dreaming may not be psychological but physiological. Rapid Eye Movement or REM sleep has been thought to help the brain process memories, but a new research in the field of ophthalmology suggests the purpose of REM sleep might be to oxygenate our corneas.

Though we can study the hard facts about our dream-brain, the dreaming mind still remains a mystery.

After losing his mentor and father-figure in a professional split with Freud, Jung suffered a tremendous psychological upheaval, a twenty-year period Stephen A. Diamond describes in his PT post “Reading The Red Book: How C.G. Jung Salvaged His Soul.”

Like Freud, Jung understood dreams to be messages from the unconscious, but rather than viewing dream images as manifest symbols of latent pathology, a storehouse of unwanted and dreaded content, Jung, through his own self-analysis, concluded that our darkest dreams might contain imagery that illustrate our internal conflicts and point to their cure as well.

In an essay on Jung, psychoanalyst Joan Chodrow describes the process by which Jung experimented with ways to restore his emotional equilibrium through dialoguing with fantasy and dream images as if these characters existed in the day-world. She writes:

“… he made the conscious decision to ‘drop down’ into the depths. He landed on his feet and began to explore the strange inner landscape where he met the first of a long series of inner figures. These fantasies seemed to personify his fears and other powerful emotions. Over time, he realized that when he managed to translate his emotions into images, he was inwardly calmed and reassured. He came to see that his task was to find the images that are concealed in the emotions.”

Jung later called the process of working with dream figures “active imagination.” In his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections, he describes terrifying encounters with his unconscious, which often threatened to overwhelm him. His gradual discovery of how to work with the fearsome material flooding his psyche has been posthumously published in The Red Book.

Written closer to the end of his life, Memories, Dreams, Reflections details perhaps more objectively Jung’s actual experience during the time of his turmoil and outlines how he came to use his own frightening encounters with his psyche to form some of his most lasting theories about conscious and unconscious material:

“… I did my best not to lose my head but to find some way to understand these strange things. I stood helpless before an alien world; everything in it seemed difficult and incomprehensible. . . . But there was a demonic strength in me, and from the beginning there was no doubt in my mind that I must find the meaning of what I was experiencing in these fantasies.

“I was frequently so wrought up that I had to do certain yoga exercises in order to hold my emotions in check. But since it was my purpose to know what was going on within myself, I would do these exercises only until I had calmed myself enough to resume my work with the unconscious. As soon as I had the feeling that I was myself again, I abandoned this restraint upon the emotions and allowed the images and inner voices to speak afresh…

“To the extent that I managed to translate the emotions into images—that is to say, to find the images that were concealed in the emotions—I was inwardly calmed and reassured. Had I left those images hidden in the emotions, I might have been torn to pieces by them…. As a result of my experiment I learned how helpful it can be, from the therapeutic point of view, to find the particular images which lie behind emotions.” (MDR, p. 177).

What if dream figures could step out of our dreams and talk to us, and tells us why they have appeared and what they want?

Using the imagination as a tool for transformation is what drew me to Jung and, later, to work with active imagination. As a writer, I inherently trust the wisdom of my unconscious mind to lead me to the story inside the story. To show me what I am not looking at, what escapes my awareness but wants to be seen. What a revelation to discover that the nightmares that wake us, shaken and despairing, might indeed be coded messages of a healing source within!

Try it yourself. Sit in a quiet place and recall a figure that has appeared to you in a dream. Talk to it. What is your second grade teacher doing in a dream? Why is she grooming a parrot? Why is this happening in your grandmother’s yard? To find out the meaning of the dream, active imagination encourages the dreamer to dialogue with dream figures in waking life. We ask and through their answers we associate what these figures might mean to us. Do they bring any stories, myths or fairy tales to mind? Looking at dream images through an archetypal and a personal lens allows us to see, alternately, the broadest and the most precise meaning of our dreams. What I’m suggesting is a simplified process but many good guidebooks exist. In the animate world of dreams, cars, trees, shoes, dogs can all speak, and what they have to say has everything to do with your life.

Recommended for further reading:Inner Work: Using Dreams and Active Imagination for Personal Growth by Robert A. Johnson

Jung on Active Imagination, edited and with an introduction by Joan Chodorow

Dreams, A Portal to the Source by Edward C. Whitmont and Sylvia Brinton Perera